My review for West of Hell first appeared in The Horror Zine. Please go there to see more reviews by me and other staff book reviewers as well as fiction, poetry, and art by many of today's established and up and coming horror-creatives. This review is reposted with permission.

My review for West of Hell first appeared in The Horror Zine. Please go there to see more reviews by me and other staff book reviewers as well as fiction, poetry, and art by many of today's established and up and coming horror-creatives. This review is reposted with permission.

I became hooked on outre Western tales after watching Gene Autry's The Phantom Empire, a 1935 serial on television (the black and white variety). To see cowboys, ray weapons of mass destruction, a mysterious subterranean empire's technology being sought after by unscrupulous businessmen, and Gene Autry getting a snappy song or two sung in-between the cliff-hanger episodes, left quite an impression on my younger mind. Since then, I have watched movies and read stories that used a weird western vibe with high expectations. The Western genre, whether old-time or saddle soap new, provides a simple backdrop for primal themes of characterization, plotting, and rip-roaring action that are ripe for mixing with the bizarre, the steampunk, the techno-goth, and the traveling horror sideshow's worth of oddities

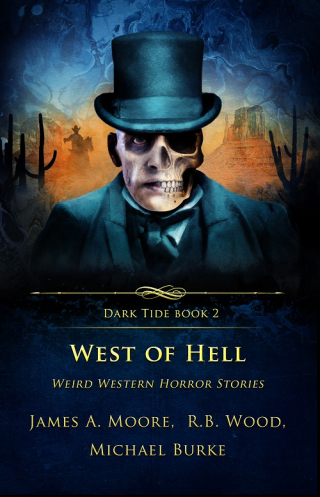

In West of Hell: Weird Western Horror Stories, three stories bring an assortment of supernatural ills to the Wild West, making for wild-in-the-sagebrush goings on to bedevil the townsfolk and other characters that James A. Moore, R.B. Wood, and Michael Burke have tasked to try and keep the peace. The beauty of this sub-genre is that it can be written as simple or as complicated as an author chooses, and here, each story focuses on the characters and their actions in dire situations with straightforward plots, which make for an enjoyably light read with enough of the supernatural to bring the weirdness home.

One notch I would put on my reviewer’s gun belt, though, is that the beginning and ending stories seem like parts of, respectively, a greater whole (meaning a novel-length adventure instead of long story). The characters are all well developed through their dialog and descriptions, but I found myself hankering for more story with them; or, at least, more adventures to come. Which, in itself, is not a bad thing at all. The middle story is neat and tidy as is, and although predictable in its outcome, still carries a solid narrative to its proper conclusion.

The first story by Moore, Ghost Dance, combines the nitty gritty Western elements we all have seen in movies and read in novels, with a supernatural red herring covering a more pressing threat reaching out to the two taciturn men, Mr. Crowley and Mr. Slate, who are called in to investigate a bizarre phenomenon that has some locals spooked. The tried-and-true elements that Moore has nailed down well are the dialog between the two men and between those around them, with few words that infer much, and the stoic demeanors of both men setting the mood: driven they are, maybe a little too crusted with experience, and always eager to get on with the matter at hand with less interference and little distraction from everyone else. Dead men walk, weaponized by a vampire, a vendetta is about to reach its end, and the trail always beckons, yearning for more adventures with Mr. Crowley and Mr. Slate (one would hope).

The middle story by Wood, The Trickster of Paradise, finds the young Thaddeus tasked with saving his townsfolk from a murderous cavalry captain bent on committing a massacre. As the captain plots his attack, White Feather, Thaddeus’s close friend, relates the legend of the White Bison, whose pictographs are found in the local cave, and how Mica, the coyote trickster spirit, became jealous of the White Bison and schemed to become more important in the eyes of the tribesmen. Both fought a mighty battle, but as to who won, that is left unanswered (well, at least until the end of the story). The legend becomes key to Thaddeus’s survival and his only hope of stopping the captain.

Wood employs nine scene shifts, separated by asterisks, which seem to hold back the story’s impact by shifting back and forth between characters and situations a bit too much. There are reasons for and against using too many scene-shifts and using them can become an easy way to avoid bridging each scene with words instead of asterisks. Unless the goal is to build dynamic tension, show time passing in a building-tension sort of way, or to quick-edit from scene to scene, like in a movie to enhance the visual impact (albeit in the mind’s eye of the reader in this case), handling them can be a challenge for any writer. My personal pet peeve aside, his plot still holds together well, and the characters remain strong and engaging with his pacing measured evenly to the end. I will give Wood credit for his competence in handling the asterisks this time around.

I do question the cost of a slice of apple pie though. In the story it is a penny. The instances where I have seen prices given, in movies or in actual menus from the period, place the cost of a slice of apple pie at five to ten cents. I am happy to arm-wrestle Mr. Wood over the matter of authenticity as long as the winner (and loser, more likely me) gets an apple pie free of charge.

The final story, Last Sunset of a Dying Age, is the longest and most complicated with many characters facing the evil that has engulfed Copper City. Burke tosses in a ronin, Ibuki Shibuya, a saloon owner, Fronnie Camus, a young, gun-happy upstart, Rattlesnake Dick, and an assortment of colorful townsfolk squaring off against an unknown (until the end, of course) horror terrorizing them. Social challenges of the time are sub-texted through Shibuya, the Japanese ex-samurai in hiding from his former master, the Chinese general store owner Zhu Shi, and their mutual dislike for one another mingled with how the townsfolk view both immigrants.

Burke also tosses in a foreshadowing with a Steyr gas seal revolver, which pegs this story taking place no earlier than 1893. Disappointingly, the gun is not pivotal to the outcome, and so loses its luster of possibilities when the monster is eventually faced down. Also disappointing is how Burke does not take full advantage of his uniquely back storied Shibuya. I cannot explain more without revealing too much, but you may see what I mean and have the same feeling.

White Feather, in The Trickster of Paradise, suffers from the same missed opportunity; though, rewriting his trajectory to the story would have required Wood to take a direction he may not have desired to explore.

Like Wood’s use of asterisks to shift scenes easily, Burke uses a time stamp instead, with date and location added for good measure in an excessive display that does not build tension or, in some cases, is not really needed where the time jump is mere minutes, not days. I kept thinking of imagined commercial breaks each time a scene heading appeared. Yes, I have watched too much television growing up. And yet, the story is still very strong because the characters and the nature of the monster add depth and interest to the plotline.

My pet peeves may not be your pet peeves, so saddle up, pardner, and do not hit that dusty trail without a copy of West of Hell in your saddle bag if you have the need for the weird in your git along. West of Hell is an enjoyable excursion into the past, where there be grievous monsters keeping the trails from being lonesome.

Comments