It was a late winter night for us in the cinematorium, the mansion’s movie theater. Zimba was stretched out on the Empire scroll sofa, already snoring away while I prepared drinks for myself and Zombos.

"Make mine a double-espresso with lots of foam," said Zombos.

He stretched out his long legs and slumped in the Chesterfield club chair.

"And don't forget the popcorn."

I loaded up the big ceramic skull o'popcorn and brought the drinks over.

I prefer to sit in the traditional theater seats that take up the first half of the cinematorium. Zombos rescued them from the Manhattan 44th Street Theater just before its demolition in 1945 to make room for the New York Times newspaper headquarters expansion.

I dimmed the lights, took a sip from my frothy mocha cappuccino, and started the movie.

Our movie this evening, The Boneyard, is a macabre but uneven mix from director and writer James Cummins. While there are watchable moments, the remainder comprised of drawn-out scenes, comical monster puppets, and dull acting by the main character gets in the way of any good scares. The premise is promising: a burned-out and overweight psychic investigator, Alley (Deborah Rose), takes on child-ghouls that eat too much. But by the time we get to the demonized, gigantic Miss Poopenplatz (Phyllis Diller) and those demon-poofle puppets, it all becomes ludicrous as in what were they thinking?

It starts with a drawn-out scene when detectives, played by veteran Ed Nelson and James Eusterman (Spaced Invaders), enter the world-weary—and messy—psychic's house. They need her help to solve a baffling case involving a mortician and what appear to be three dead children he’s been hiding. They draw their guns dramatically when she doesn't answer, but why do that? She finally turns up after an endless search of the house we’re forced to follow, room by room. When they fail to enlist her aid they leave.

Later that night she has a disturbing vision involving a putrescent little girl with lots of long, stringy blond hair, who wants very much to hug and thank her for her help in a previous case. This promising scene has nothing to do with the story, but it does cause Alley to change her mind about helping the detectives. Deborah Rose's lifeless acting is flatline throughout.

At the police station, Alley and the detectives listen incredulously to the interrogation of the mortician. He explains how his family has, for three centuries, kept the three child-sized ghouls—he calls them Kyonshi—from devouring living people by feeding them body parts garnered from the funeral home's cadavers. Kyonshi, or hopping vampires, are not flesh-eating ghouls, I think, so the use of the term here may be a stretch.

Next, it's off to the soon-to-be-closed coroner's building where the story kicks into low gear, but not before we are subjected to a confusing flashback experienced by Alley, followed by an interminable dialog between the two detectives standing in a hallway. Show and do aren’t buzzwords this director adheres to.We also meet Miss Poopinplatz. She manages the front desk along with her annoying poodle.

Alley has a vision of the three little ghouls awakening downstairs in the morgue with all the tasty attendants (Norman Fell among them) in the next room. Little tension is generated as boy-this-weight-does-slow-me-down Alley clumsily makes her way downstairs to warn the lab attendants of their impending Happy Meal status.

When she finally does reach the morgue, chewed up dead bodies are strewn everywhere. Gobs of blood splatter the floor and the little hellions are still chomping away—especially one who gustily attacks an exposed rib-cage. This is the only good gore scene in the movie. My guess is the budget was blown at this point. All this explicit gruesomeness is a sudden and unexpected jolt in an otherwise static movie. Bodies hang limply from shelves, carried there by the three child-ghouls. Sitting atop a battery operated forklift, the medium-sized ghoul feasts on a pathologist while another rips apart another body. The smallest ghoul has dragged the bloody corpse of a Pathologist to the fifth level of shelves. It eats an ear off and then snacks on a finger. The creature makes a happy purring sound as it chews. Its gaping mouth continues to rip a chunk from a pathologist's side.

Mayhem ensues as survivors try to escape. They trap and kill one ghoul, but he manages to stuff part of his skin—it’s disgusting to watch—down Poopinplatz's throat, turning her into a very tall and pop-eyed Muppet-like puppet monster that desperately needed more money and a better design to be convincing. The comical nature of the puppet derails the momentum established by the morgue scene.

Poopinplatz's dog, Floosoms, licks up bubbling yellow ichor oozing from one expired ghoul and quickly turns into a man-in-a-suit demon Muppet Floosoms. A horrified girl rescued from the previous morgue attack laughs when she sees this comicalpoodle monster.

Who wouldn’t?

The action is stopped cold, again, for another long and bewildering dialog as Cummins gives the ENTIRE background of the girl who survives the morgue attack. The action picks up again with an Alley and demon-Floosoms confrontation and some dynamite.

If Cummins used a lot less dialog, and Deborah Rose’s acting were a lot lighter, and the three child-ghouls were given more screen time to terrorize, The Boneyard could have, would have, been a scarier movie even with Phyllis Diller mugging it up as Poopinplatz.

Take a look, fast forward a lot, and you’ll be fine: the morgue smorgasbord scene is worth a look at least.

In our never-ending quest to bring you the most fun apparel any zombie-lover -- that's you! -- can wear, Chindi spotted this chic t-shirt that reminds us of how much we love to eat fresh at Subway, and how much we love to watch zombies eat fresh, too.

In our never-ending quest to bring you the most fun apparel any zombie-lover -- that's you! -- can wear, Chindi spotted this chic t-shirt that reminds us of how much we love to eat fresh at Subway, and how much we love to watch zombies eat fresh, too.  Zombos Says: Very Good (but weird)

Zombos Says: Very Good (but weird)

Zombos Says: Very Good

Zombos Says: Very Good "Didn't you listen to the director's commentary? He mentions this film came from his own experience with head trauma after a serious auto accident. He goes on to mention how he worked through Kubler-Ross' stages of grief and—"

"Didn't you listen to the director's commentary? He mentions this film came from his own experience with head trauma after a serious auto accident. He goes on to mention how he worked through Kubler-Ross' stages of grief and—" "When he returns home, he has to deal with a neighbor that wants the house demolished so he can buy the property, a massively flooded basement, a ruined relationship with old-flame Mary, the presence of a mysterious person dressed in the parka, and trying to keep the house from being torn down."

"When he returns home, he has to deal with a neighbor that wants the house demolished so he can buy the property, a massively flooded basement, a ruined relationship with old-flame Mary, the presence of a mysterious person dressed in the parka, and trying to keep the house from being torn down." "Yes, there are nice shock cuts that keep the tension going, along with brooding scenes of the house and its desolate rooms. No splatter gore, or naked screaming nubile woman to distract you from the carefully paced mood," agreed Zombos. "The focus stays on George, his depression over his current state of affairs, and failure to achieve his goals, and his growing realization of something just out of the corner of his eye waiting to poke a finger in it. I daresay his encounter in the basement with the dark hair bobbing up out of the water, presumably attached to a head just out of sight, would unsettle anyone's nerves."

"Yes, there are nice shock cuts that keep the tension going, along with brooding scenes of the house and its desolate rooms. No splatter gore, or naked screaming nubile woman to distract you from the carefully paced mood," agreed Zombos. "The focus stays on George, his depression over his current state of affairs, and failure to achieve his goals, and his growing realization of something just out of the corner of his eye waiting to poke a finger in it. I daresay his encounter in the basement with the dark hair bobbing up out of the water, presumably attached to a head just out of sight, would unsettle anyone's nerves." "Those scenes do not need to be very frightening," said Zombos. "They do need to unsettle and confuse George and us, and that's what they do."

"Those scenes do not need to be very frightening," said Zombos. "They do need to unsettle and confuse George and us, and that's what they do." "Indeed," I said. "I'm just not sure if I would classify this film as horror, though."

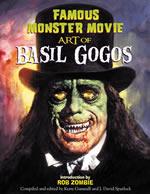

"Indeed," I said. "I'm just not sure if I would classify this film as horror, though." So there you stand, scratching your severed head in dismay; what gifts to get that ho-ho-ho-so difficult horrorhead in your family? Why suffer the hordes of zombiefied holiday shoppers, overwhelmed store employees, and bargain bins of the damned when you can sail down the Amazon in shopping comfort while sipping your favorite frothy beverage? To help you with your gift buying, Zombos Closet presents the first annual list of bloody best books any fan of horror cinema would die and come back for, again and again.

So there you stand, scratching your severed head in dismay; what gifts to get that ho-ho-ho-so difficult horrorhead in your family? Why suffer the hordes of zombiefied holiday shoppers, overwhelmed store employees, and bargain bins of the damned when you can sail down the Amazon in shopping comfort while sipping your favorite frothy beverage? To help you with your gift buying, Zombos Closet presents the first annual list of bloody best books any fan of horror cinema would die and come back for, again and again.

Zombos Says: Very Good

Zombos Says: Very Good Slither is a well-crafted mix of computer animation, traditional puppetry, rubber and gook special effects, and slimy, horrific make-up artistry that, combined with a witty, fast-paced script and bread and butter cinematography, is a fun and disgusting romp at the same time.

Slither is a well-crafted mix of computer animation, traditional puppetry, rubber and gook special effects, and slimy, horrific make-up artistry that, combined with a witty, fast-paced script and bread and butter cinematography, is a fun and disgusting romp at the same time.

"Not another new horror magazine?" asked Zombos.

"Not another new horror magazine?" asked Zombos.