This extensive 15 by 22 inches movie pressbook for Black Zoo is well thought out, and even includes promotional coverage to be done through Famous Monsters of Filmland and other monster magazines.

« June 2014 | Main | August 2014 »

Entries from July 2014

July 07, 2014

July 04, 2014

July 03, 2014

July 01, 2014

Subscribe to Weekly Email for New Posts!

Go To...

Read My Book on Kindle

I Like to Talk

Categories

- Art/Animation (32)

- Authors (28)

- Azteca/Mexican Lobby Cards (779)

- Bloggers (48)

- Books (Bad) (2)

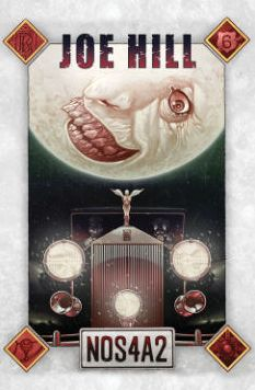

- Books (Fiction) (51)

- Books (Graphic) (33)

- Books (Non-fiction) (31)

- Comics/Manga (85)

- Convention/Event Programs (8)

- Death (13)

- Documentaries (11)

- Freaks/Geeks (5)

- Gift Ideas (12)

- Halloween (Memories) (54)

- Halloween Candy (36)

- Halloween Costume (70)

- Halloween Light-Ups (16)

- Halloween Novelty (91)

- Halloween Paper (63)

- Haunt Attractions (8)

- Horror Hosts (29)

- Kinema Archives (51)

- LOTT D (66)

- Magazine Morgue (261)

- Model Kits/Figures (10)

- Monster Laffs (10)

- Movies (Bad) (49)

- Movies (Drive-in) (31)

- Movies (Ghostly) (19)

- Movies (Gore) (9)

- Movies (Horror) (90)

- Movies (Indie) (33)

- Movies (Non-horror) (9)

- Movies (Slasher) (12)

- Music/Radio (13)

- Pictures (102)

- Pressbooks (Horror, Sci Fi, Fantasy) (666)

- Pressbooks (Non-Horror) (198)

- Reflections (58)

- Short Stories (2)

- Superheroes (9)

- Toys/Games (23)

- Trading Cards (16)

- TV/PC (28)

- Universal Monsters (21)

- Vintage Days (26)

- Wild West Weird (6)

- Zoc's Desk (9)

Significant Others

Other Others

Copyright Notice

From Zombos' Closet by John Michael Cozzoli is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License.

Based on a work at http://www.zomboscloset.com.- Copyright© 2006-2023

From Zombos' Closet's fictional characters and personal blog posts are created and copyrighted by JM Cozzoli. Additional content is copyrighted by the respective contributors and owners of that content. From Zombos' Closet is a non-commercial site for the enjoyment of fans of the fantastique, the horrifying, the trashy, and the sublime.