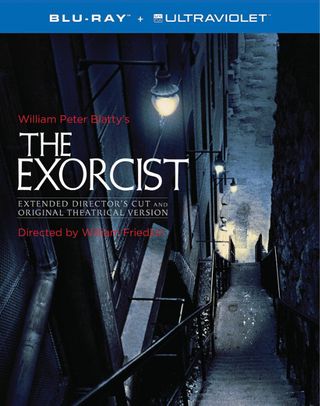

It's something you would be hard pressed to write in fiction: small Pittsburgh-based production company gets bored with making television spots that include Mr. Rogers' Gets a Tonsillectomy, beer commercials, and a Calgon commercial knocking off Fantastic Voyage and decides to produce THE MOVIE that would change the face of horror.

Of course George A. Romero, John Russo, and Russ Streiner never realized the THE MOVIE part at the time; and we can forgive them for first wanting to do Romero's screenplay Whine of the Fawn, a Bergmanesque snoozer. But thank god for us reality reared up and kicked sense into them that a horror movie was an easier sell to their prospective investors. The rest is history. And a rich and inspiring history it is.

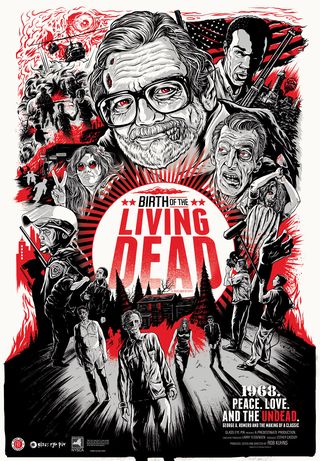

Bob Kuhns captures this inspiring history to a worthwhile degree in his lively documentary Birth of the Living Dead, giving us the skinny on how a small production company moved from small fries ad spots to buying a 35mm camera in hopes of baking a hot potato money-making movie. So what if it didn't make much money for Romero or his investors? It sure as hell made tons of money for everyone else, and the nightmare it started is still going gangbusters across the zombie-stomping globe, from commercials (ironic, right, given Romero's start?), to television series, to an endless stream of mall crawls, village invasions, movies, and merchandising.

That movie, Night of the Living Dead, originally written as a comedy, created the tropes, themes, styles, and scares that are constantly revisisted and expanded on today. But you already know that. Its cheapo black and white starkness, its non-actors who could actually act and ad-lib their lines, and Romero's simple screenplay delivered through sharp editing, still chills us with its flesh-eating zombies (or as Romero originally called them, "Ghouls") and their unending aim to eat anything not moving fast enough away from them. Toss in that eerie, nerve-tingling, music score and the all-hell-breaks-loose-everybody-for-themselves dynamic with its marked deviation from the usual supernatural, psycho, and scientific horrors playing theaters and drive-ins up to 1968, and it's no wonder the wise-ass matinee kids--waiting to goof around and chuck their popcorn at the screen the minute the credits rolled--didn't know what hit them between the eyes. Neither did the critics whose ire was boundless. Romero and company set out to make Night of the Living Dead "as balsy a horror film as we could make." Their gorilla filmmaking did just that.

Night of the Living Dead premiered on October 1, 1968 at the Fulton Theater in Pittsburgh. Nationally, it was shown as a Saturday afternoon matinée – as was typical for horror films at the time – and attracted an audience consisting of pre-teens and adolescents. The MPAA film rating system was not in place until November 1968, so even young children were not prohibited from purchasing tickets. Roger Ebert of the Chicago Sun-Times chided theater owners and parents who allowed children access to the film with such potent content for a horror film they were entirely unprepared for. "I don't think the younger kids really knew what hit them," he said. "They were used to going to movies, sure, and they'd seen some horror movies before, sure, but this was something else." According to Ebert, the film affected the audience immediately. (Wikipedia)

Although Kuhn invokes enough authoritative talking heads to establish this fact (among them are Gale Ann Hurd, Larry Fessenden, Jason Zinoman, Elvis Mitchell, and Chiz Schultz), it's Romero's ingenuous reminiscenses and witty insight we salivate over. The way he explains it, it sounded like the whole undertaking was a lark. A lot of hard, crazy work, but a lark.

Splicing in Vietnam War footage, scene clips, animated segments, 1968 race riots footage, and a side trip as teacher Christopher Cruz shows Night of the Living Dead to his young students in his Literacy Through Film Program class (yes, the times have indeed changed), we always come back to Romero as he describes the shooting's trials and tribulations at the abandoned farmhouse they rented, and the final nerve-racking search for a distributor. Everyone involved wore muliple hats to pitch in: Bill "Chilly Billy" Cardile joined the cast as a news reporter and gave free publicity for the movie through his Chiller Theatre horror hosted show; aerial shots of zombies stumbling in the fields were provided courtesy of hitching a ride with the local news chopper; local sheriffs with their police dogs joined in the zombie hunting with gusto; Chuck Craig, a real newsroom reporter played a fictional newsroom reporter, writing his own news copy for the movie, making it play uncomfortably too real.

With the movie in the can and ready to sell, distributors presented more challenges because they wanted a happier ending. No way was Night of the Living Dead in any way a movie that could end happily. Walter Reade eventually took the chance, with depressing ending and all gore scenes intact, but screwed up big time when they inadvertantly dropped the copyright notice off the new prints when changing the original title of Night of the Fleash Eaters to Night of the Living Dead. How many millions of dollars did Romero and his investors never see because of this simple oversight? As Night went public domain, their profits went out the door. Sure, Romero can laugh it off now, but it must still hurt. A lot.

The usual social and political instigations and social backdrops for how and why Night of the Living Dead eventually hits every nerve just right is touched on but glossed over by Kuhn and never fleshed out. He doesn't plumb those connections, just their intimations. Sure, maybe it was luck and timing; maybe Romero was too lazy to change the role of Ben, written for a white actor but played by a black one instead; or maybe, subconsciously, Romero and company weren't really taking shortcuts but tapping into some Jungian primalcy without realizing it, fueled by their annoyance at how much the 1960s promised to change the world's social order, but failed to.

So damned if they didn't just go ahead and change the world on their own instead.