O, creator of Hecate, Damkina, Marduk's Messenger ... tem-khepera, khnemu ... Beelzebub in the netherworld ... Satan in Gehenna ... Controller of seven thousand and seven curses and talismans ... and who is known to obedient desciples as Gangida ... hold all your powers and those of your do-bidders ... and their familiars ... and cast a protecting shield above those gathered present...Pull back from airy bodies those vested with evil ... grant, O, magnificent one, no harm from the spells about to be witnessed. Direct them not! This faithful servent begs for Thy favor! Eftir irne-zet! Now with a free mind and protected soul, we ask you to enjoy Burn Witch, Burn!

Fritz Leiber's first novelette, Conjure Wife, originally appeared in the April, 1943 issue of Unknown Worlds , a pulp magazine. An expanded and revised version was published by Twayne Publishers in its Witches Three anthology in 1952, then issued as a stand-alone novel in 1953. Both hardcover and paperback editions, by a variety of publishers, continue in print to this day. Leiber's story is widely acknowledged to be a classic of modern horror fiction, included in David Pringle's Modern Fantasy: The 100 Best Novels, and in Fantasy: The 100 Best Books by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock. In The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, David Langford described it as "an effective exercise in the paranoid." Science Fiction author Damon Knight wrote:

"Conjure Wife, by Fritz Leiber, is easily the most frightening and (necessarily) the most thoroughly convincing of all modern horror stories... Leiber develops [the witchcraft] theme with the utmost dexterity, piling up alternate layers of the mundane and outré, until at the story's real climax, the shocker at the end of Chapter 14, I am not ashamed to say that I jumped an inch out of my seat...Leiber has never written anything better."

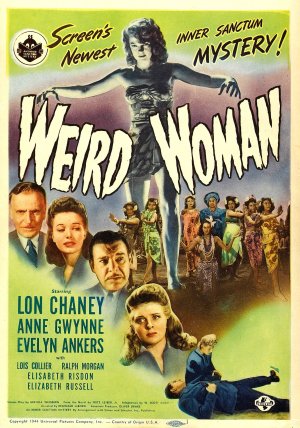

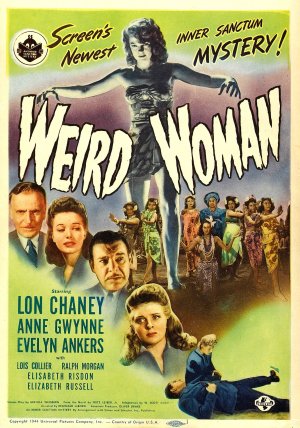

It was the original pulp novelette on which the screenplay of its first film version, Weird Woman (1944), was roughly based. Universal had initiated a B unit-produced series inspired by, and copying the name of, the popular radio series The Inner Sanctum. At the time, the series was in it's heyday and a series of Inner Sanctum books was equally popular. The Universal series, however, was promoted as a separate and original entity.

It was the original pulp novelette on which the screenplay of its first film version, Weird Woman (1944), was roughly based. Universal had initiated a B unit-produced series inspired by, and copying the name of, the popular radio series The Inner Sanctum. At the time, the series was in it's heyday and a series of Inner Sanctum books was equally popular. The Universal series, however, was promoted as a separate and original entity.

The first film of the series was Calling Dr Death (1943), which featured Lon Chaney, Jr, who went on to star in the entire series over the next couple of years. The director was Reginald Le Borg, under contract to Universal. Le Borg and Chaney had previously made The Mummy's Ghost (1943) and, after Calling Dr Death, moved on to the second of the Inner Sanctum series, Weird Woman. The series continued with Dead Man's Eyes (1944, again directed by Le Borg), Pillow of Death (1944), The Frozen Ghost (1945) and Strange Confession (1945). Of the entire Inner Sanctum series, Weird Woman is generally considered to be the best.

Weird Woman's screenplay was prepared by Brenda Weisberg and W. Scott Darling. The credits read "Screenplay by Brenda Weisberg, from the novel by Fritz Leiber, Jr" and "Adaption by W Scott Darling." The title of Leiber's novelette is not mentioned. Le Borg was handed the script a week before production was to begin and prepared for filming without reading the novelette. Via promotion, theater-goers were reminded that Lon Chaney, Sr was known as "The Man of a Thousand Faces," so now his son, Chaney, Jr was touted as "The Man with the Voodoo Voice." According to Weird Woman's pressbook, Chaney developed this talent in order to "project the voice of the supernatural," supposedly using a trick of ventriloquism taught to him by his father. Evelyn Ankers, the heavy of the story, carried the label "The Queen of the Horror Films."

Chaney was cast as Professor Norman Reed, a teacher of sociology at Monroe College in New England and the author of 'Superstition vs Reason and Fact.' In the novelette, his name is Norman Saylor, a teacher at Hempnell College who is preparing a paper, 'The Social Background of the Modern Voodoo Cult.' Ann Gwynn plays his wife, Paula (Tansy Saylor in the novelette), and Evelyn Ankers is Ilona Carr (Mrs. Carr in the novelette, referred to at one point as "...that libidinous old bitch"). It is not clear which of the female leads can truly be referred to as the weird woman. Since several women in the cast are involved in some sort of witchcraft, the film could more appropriately be titled Weird Women.

Chaney was cast as Professor Norman Reed, a teacher of sociology at Monroe College in New England and the author of 'Superstition vs Reason and Fact.' In the novelette, his name is Norman Saylor, a teacher at Hempnell College who is preparing a paper, 'The Social Background of the Modern Voodoo Cult.' Ann Gwynn plays his wife, Paula (Tansy Saylor in the novelette), and Evelyn Ankers is Ilona Carr (Mrs. Carr in the novelette, referred to at one point as "...that libidinous old bitch"). It is not clear which of the female leads can truly be referred to as the weird woman. Since several women in the cast are involved in some sort of witchcraft, the film could more appropriately be titled Weird Women.

Ann Gwynne proves to be the victim-weird-woman while Evelyn Ankers proves to be the evildoer-weird-woman. Promotion featured a provocatively sinister-looking Anne Gwynne posed in a sarong, hands outstretched and exuding a diabolic nature that is not developed as such in the film. Yet the term 'Weird Woman' could ultimately refer to woman-kind in general, as it is with the women in the plot who are bewitched and bewitching. Reportedly, the confrontation sequence between Gwynne and Ankers proved to be a difficult undertaking because they were such good friends.

Ann Gwynne proves to be the victim-weird-woman while Evelyn Ankers proves to be the evildoer-weird-woman. Promotion featured a provocatively sinister-looking Anne Gwynne posed in a sarong, hands outstretched and exuding a diabolic nature that is not developed as such in the film. Yet the term 'Weird Woman' could ultimately refer to woman-kind in general, as it is with the women in the plot who are bewitched and bewitching. Reportedly, the confrontation sequence between Gwynne and Ankers proved to be a difficult undertaking because they were such good friends.

Weird Woman reached a new audience when it was included as part of the original SHOCK! package of 52 Universal titles released to television in 1957.

After the 1953 publication of the reworked Conjure Wife in hardcover, it was to be the inspiration of the definitive screen version nine years later. In the meantime, a Twilight Zone episode titled The Jungle appeared on the airwaves on Dec 1, 1961. It was based on a short story of the same name by Charles Beaumont, first published in 1954 in If magazine. It later appeared in Beaumont's collection, Yonder (1958).

Plot-wise there were similarities to Leiber's novel, with a few touches of Val Lewton's Cat People tossed in. The story involves actors John Dehner and Emily McLachlin in a tale of a hydroelectric company executive whose firm is moving into an African nation to build a dam. The native residents don't take to the idea. An early sequence focuses on the (conjure?) wife whose husband discovers and subsequently destroys her magic charms and talismans. All, save one, are tossed in a fireplace. They go up in little puffs of smoke and make the wife terribly upset. Other elements common to this TV episode and the later Burn Witch, Burn crop up, such as Dehner's pursuit by an invisible force. His ultimate demise happens at the teeth and claws of a ferocious beast (here a lion) who inexplicably manifests itself after first appearing in stone form. No credit is given to Leiber.

In London the following year, two weeks before the cameras were to roll, writer George Baxt was handed a script written by Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont. Director Sidney Hayers was dissatisfied with what he felt was an unworkable treatment of Leiber's novel and turned to Baxt for help. Hayers and Baxt had previously worked successfully together on Circus of Horrors (1960).

Like Le Borg almost two decades earlier, Baxt had not read Conjure Wife. His task was to take the Beaumont/Matheson script and 'doctor' it, removing what was felt to be inane dialogue. For example, the professor's wife is confronted by her husband, who demands that she give up her witchcraft and voodoo and destroy her magic symbols, talismans, charms and so forth. An exact quote from the novel's text, also in the script, was "But couldn't I just quit by degrees?" This was changed to, "Couldn't I just taper off?"

In an interview I had with him in his NYC apartment, Edgar Award winning author George Baxt related his involvement with what was to eventually released as Burn Witch, Burn:

In an interview I had with him in his NYC apartment, Edgar Award winning author George Baxt related his involvement with what was to eventually released as Burn Witch, Burn:

"It started with a call from an agent. I was living in London at the time. British director Sid Hayers had a script based on Fritz Leiber's Conjure Wife that was prepared by Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson. The working title was Night of the Eagle. I previously prepared the screenplay for Circus of Horrors, also directed by Sid. The association was a good one. Both Beaumont and Matheson were established, well-known screenwriters, yet they came up with an unfilmable treatment. I was given two weeks to deliver a product and, needless to say, I had to work quickly. I had never read Leiber's novel. Work on the script continued during principal photography with additional pages and revisions delivered to the set on a daily basis.

(Note: I didn't ask him if Hayers or Baxt had seen and were familiar with Weird Woman of 1944)

"The original actress who was to play Tansy was June Allyson. Because of personal problems she was dropped and replaced by Janet Blair. Peter Wyngarde (Norman Taylor) was also cast as a replacement when the original actor became ill. Additions to the script that I was responsible for were the sequence in the graveyard and Tarot-card-burning scene. I thought the graveyard scene was handled well on the screen. Sid wanted me on the set throughout the shooting of the faculty bridge game. Margaret Johnston (Flora Carr) was the heavy of the story and it was important to the plot that she be positioned within the frame, appearing menacingly. Throughout she was constantly casting leery glances at Peter Wyngarde. The whole sequence was put on film in about an hour. I suggested at one point to place the camera behind the fireplace shooting out at the players (The Old Dark House-type of shot). As far as the eagle pursuit sequence goes, I originally didn't like the way it was handled, looking phony. Now, I think it was impressive."

Mention should also be made of the eagle that assays the role of the giant 'demon bird' who pursues Peter Wyngarde. It was a golden eagle named Lochinvar, trained especially for film and TV roles. The shot of the eagle bursting through the door was achieved by punching a glove puppet through a miniature of the door. There are only a few frames of this sequence before a very quick cut to a shot of an actual eagle in a miniature of the hallway, but the shape of a hand and wrist can just be made out in silhouette. Also, when the eagle is briefly shown in flight, a thin cable is visible attached to one of it's feet, guiding it's path. All in all, the complete sequence was effective for a film of it's day.

Pressbooks for Weird Woman and Burn Witch, Burn both emphasize supernatural elements of voodoo, witchcraft, and superstitions. Theatrical prints for the American release usually contained a pre-credit opening incantation (quoted at the start of this article), read by Paul Frees. It is heard over a totally blank screen, designed to expel 'evil spirits' from the theater, and psychologically prepare the audience for the story.

At one point in the story Norman jokingly refers to Mrs. Carr as "That old warlock." An interesting point since traditionally a warlock is what a male witch was referred to. Later in the story Norman catches Tansy with her charms and talismans. Angrily she states, "...yes, I'm a witch!" The 'not for publication' synopsis mentions a final shot of Tansy clutching the lucky charm behind her, the only one she managed to save. However, the actual final image is of the audio tape of one of Norman's classroom lectures unraveled on the ground right after the death of Mrs. Carr. The not-so-subtle question Do You Believe? is superimposed over the shot (instead of the simple 'The End' title that is in the British version).