Zombos Says: Sublime

Listen to this Movie Review

Our times have indeed changed.

Our psyches have succumbed to accepting serial killers and terrorists walking the daylight hours just as easily as Dracula hunts through the night. The simple truth is we no can no longer be scared by the black and white monsters of yesterday: or spook show scared by mad scientists and marauding apes; or Frankenstein's Monster scared; or stalked by Bela Lugosi through a cemetery scared. We need victims suffering more pain and more terror in movies now for our scares: we need to see their limbs and minds pulled apart in ever more creative and disgusting ways to lessen the real horrors snarling at us daily, ready to pounce without warning. We've overdosed on real fear as it constantly gnaws away at us like Lovecraft's rats in the walls, until we need another fix that's stronger than the Wolf Man's bite or seeing baby zombies dancing on YouTube.

The monsters no longer live on Maple Street: they moved in on my street, and your street, and every other street in the world. They began moving in sometime around 1968, after the Vietnam War had taken its toll on our senses while it held us prisoner by its extensive primetime television coverage, giving Dracula and the Mummy serious competition for our scares.

George Romero shocked us with a visceral, unrelenting horror lumbering ever closer to our homes, but even before him directors like Herschell Gordon Lewis were upping the body count and buckets of blood with gusto; or telling us Uncle Charlie isn't the person you think he is until we finally believed it. Blame Alfred Hitcock's Shadow of a Doubt and Psycho for instigating this change from our comfortably distant monsters to the normal-looking family dismemberer, or the quietly deadly person next door with long pork in his fridge, or the nascent mass murderer down the block with the huge gun collection.

It took Peter Bogdanovich's Targets to solidify this change. At a time when major political figures were being assassinated, social unrest had hit its deadly zenith, and the Mai Lai Massacre unraveled moral certainty, Targets' spree-killer Bobby heralded the new monster model, the kit Aurora never got around to making: the unassuming neighbor with a wish for death on his lips—lots of deaths—and a fetish for guns. Lots of guns.

The greatest fear is the one breathing down your neck with its hands in your pockets. You can ask all the questions you want, but no answers will come. They never do. So you make up your own answers to satisfy yourself that you know WHY. But you never really do. There is no real WHY. There's only how, and when, and who will be next.

Clean cut, upper middle-class Charles Whitman went on a shooting spree at the University of Texas at Austin, indiscriminately killing or injuring anyone he could target in his 4x Leopold Scope, mounted on his hunting rifle. Why he did that on an ordinary day in August of 1966 is anyone's guess.

Maybe he had a brain tumor. Maybe he had a ruptured family life with a domineering, perfectionist father. Maybe he had an unhappy marriage. Maybe he had too many guns.

Bobby Thompson (Tim O'Kelly), the indiscriminate, sniping murderer in Targets is Bogdanovich's Whitman. Bobby's unhappy but he doesn't know why. Bobby wants to murder his family, but he's not sure why. Bobby needs to shoot as many people dead as possible. We don't know why.

Not knowing why is the true horror in Targets, and a brilliant understatement by Bogdanovich. The remaining horror is death; all the death Bobby deals through his targeting scope and the fear of death the aged and tired Byron Orlok (Boris Karloff) feels breathing down his neck. Roger Corman may have insisted Bogdanovich use Karloff's contracted time, and the extra minutes of footage from Karloff's movies (The Terror and The Criminal Code) to pad the movie's running time, but Bogdanovich turns this budget thriller into a masterpiece of terror by incorporating those minutes as essential extensions to his story while allowing Karloff's notoriety to flesh out Orlok's credibility. They enhance the movie's theme of fait accompli death; the irreconcilable one brought about by Bobby's hand and the impending one soon to overtake Orlok, who, at the end of his career is closer to Death's hand and now questions the worth of his life and career. Both men are preoccupied with death, but Orlok turns inwardly to shut off his future while Bobby turns outwardly to shut down his past.

Orlok doesn't want to do any more movies. He turns down Sammy's (Peter Bogdanovich) next script and suddenly decides to retire from the screen. Bobby doesn't want to keep living the way he does so he starts planning his family's murder and his killing spree. A glimpse into his car trunk reveals an arsenal of firepower, lovingly arranged like butterflies stuck on needles in a glass showcase to be admired. From a gun shop Bobby examines his new gun scope closely. He chances on seeing Orlok across the street and lines up the famed horror actor in the crosshairs. Afterwards, Bobby eats candy bars and blasts his car radio while he drives around to find the perfect killing ground along the Reseda Freeway. Orlok heads off to enjoy a quiet dinner, celebrating his retirement from movies where, as he says, anyone can be painted up to scare the audience these days.

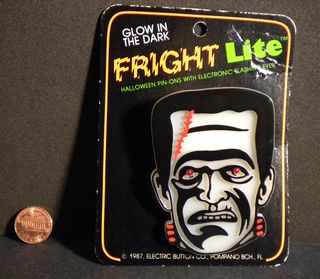

Remember how Karloff felt when the Frankenstein Monster became a prop that anyone could dress up as? He gave up the role after Son of Frankenstein because of that.

Sammy persists. He shows up in Orlok's hotel room, script in hand. He gets drunk with Orlok as they watch The Criminal Code. Both sleep it off. Orlok's assistant Jenny (Nancy Hsueh) convinces Orlok to reconsider Sammy's movie offer. And Orlok finally agrees to do the personal appearance he promised for the Reseda Drive-In for the screening of one of his old movies, The Terror.

Orlok quickly becomes annoyed by the questions and answers prepared for him by the interviewer for the screening (Sandy Baron) and recommends he tell a story instead. Bogdanovich pulls the camera in close as Orlok, now really Karloff the Uncanny, relates the ironic twist of fate in An Appointment in Samarra. Not only does Bogdanovich pay homage to a master craftsman, whose name is synonymous with horror cinema, but he uses this wonderful opportunity to further his theme of death; and Karloff tells this story in one take (the production crew clapped when he was done).

Both Orlok and Bobby have an appointment to keep at the Reseda Drive-In.

Orlok arrives in his limousine and waits for his interview. Bobby sees an opportunity to evade the police and hides behind the big screen after his earlier rampage sniping at drivers on the Reseda Freeway is interrupted by the police searching for him.

One by one he begins to shoot people in the audience, until someone notices what's going on and spreads the warning that there's a sniper. Cars begin to leave, prompting Orlok to joke how much they enjoy his movie. Bogdanovich shows scenes of Orlok in The Terror in-between scenes of Bobby killing drive-in patrons, contrasting old horror with new. One scene, the one which upset me when I first watched Targets—and still does—involves a dome-lighted car interior, a crying youngster, and his unfortunate father. We see the youngster's face first, the tears, the terror on his face; then we see his father shot through the head: unexpected death in an unsuspecting place. In this single moment, Bogdanovich shows us the most important thing we need to know about true horror, which doesn't come from seeing the monster, but from seeing the monster's aftermath.

Orlok, seeing Bobby has a rifle, goes after him with his cane. Bobby, confronted by an approaching Orlok on the drive-in screen behind him and the real one in front of him, becomes confused. Orlok knocks the gun from Bobby's hands, asking himself "Is this what I was afraid of?"

As the police handcuff Bobby, he boasts he rarely missed. And isn't that what we are all afraid of?

Five questions asked over a glowing Jack o'Lantern, under an Autumn moon obscured by passing clouds...in between mouthfuls of candy corn...Johnny Boots of Freddy In Space has this thing for Freddy and Halloween. Is it just me, or do you think this photo is as creepy as all Hell, too?

Five questions asked over a glowing Jack o'Lantern, under an Autumn moon obscured by passing clouds...in between mouthfuls of candy corn...Johnny Boots of Freddy In Space has this thing for Freddy and Halloween. Is it just me, or do you think this photo is as creepy as all Hell, too?