Another rare fanzine from Professor Kinema's archives, Fantasy Magazine, July 1935, was given to the Professor by Forrest J. Ackerman. Ackerman's article and note can be seen on page 10.

For comic book reader users: Download Fantasy Magazine 1935

Another rare fanzine from Professor Kinema's archives, Fantasy Magazine, July 1935, was given to the Professor by Forrest J. Ackerman. Ackerman's article and note can be seen on page 10.

For comic book reader users: Download Fantasy Magazine 1935

Posted at 11:50 AM in Kinema Archives, Magazine Morgue | Permalink | Comments (0)

Betsy Palmer: Nov 1, 1926 - May 29, 2015

Betsy Palmer: Nov 1, 1926 - May 29, 2015

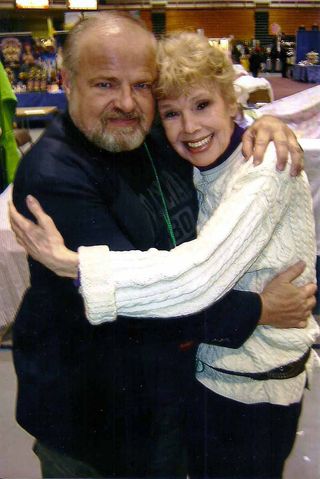

She was petite, very pretty, and had one of the most endearing smiles of anyone I had ever met.

We met during, for what turned out to be, the final time I was involved with I-Con (I-Con 27: Apr 4-6, 2008). I had managed to interest Betsy Palmer to be a guest. Early on the Friday that was the first day of I-Con I drove into Manhattan and picked her up at her apartment on West 85th Street. On the way back I was to pick up another I-Con guest: Will Hutchins (Sugarfoot in the Cheyenne television series). During the ride to his home in Nassau, Long Island, we chatted pleasantly.

My first, brief, encounter with her was at a trade/paper show in Manhattan a few years earlier. Not unexpectedly, she didn't remember our first meeting. During the ride we spoke of my earliest reminiscences of her as a guest panelist on TV's To Tell the Truth (1957 to 1965) and I've Got a Secret (1955 to 1967). We also touched upon the other well known films and TV shows she had appeared in, mainly those in the 1950s.

Off course, we got around to the role that she'd probably be best remembered for: Pamela Voorhees, Jason's unstable mother, in Friday the 13th (1980). Her appearance in this film was the reason for her attending a science fiction convention as a guest.

Discussing this film always made her wince. The main reason she accepted the part (after not appearing in a theatrical film since 1959) was because her car had broken down while driving on I-95 in Connecticut. Needless to say, this was one mega-unpleasant experience for her. She was desperately in need of a new car when her agent suggested she do the film. The original actress approached for the role was Estelle Parsons. Naturally, the part "wasn't right for her...too much violence." Nor, one suspects, did Parsons have a burning need for a new car.

When Betsy first looked over the script, she commented that it "was the worst piece of shit" she had ever read. After completing the film she continued to call the film..."a piece of shit." During our discussions, both during our car ride and with interested fans at I-Con, she steadfastly maintained that it was a "piece of shit." She was guaranteed $1000 per day and worked on the film for 10 days. Her on-screen time lasted for about (ironically, for real) 13 minutes. In the first 70 minutes of the film, her character was actually performed by a male stand-in. This worked because she was not supposed to be recognized.

To the I-Con fans she related the story of her car breakdown and agreeing to do the film for the $1000 per day. She said, "Nobody is ever going to see this. It will come and it will go. I was mostly interested in purchasing a Volkswagon Scirocco." One major fact I brought up and strongly dwelled upon with her was that whether or not she thought Friday the 13th was truly "a piece of shit," the result of her involvement with it had made her a bonafide cult celebrity. I also made the point of how that fact placed her miles ahead of many other performers who had appeared in other popular-- and probably-- 'piece of shit' films.

Professor Kinema standing over Will Hutchins and Betsy Palmer.

Professor Kinema standing over Will Hutchins and Betsy Palmer.

The original Friday the 13th was the one entry of the series she was actively involved with. However, when the sequel, Friday the 13th Part II (1981) was being lensed in Connecticut, she was hired for a one day shoot of a few scenes in front of a black screen--in California. Archival footage of her turned up in Friday the 13th Part III (1982), Friday the 13th: the Final Chapter (1984), Friday the 13th: No Man's Land (2010), and the TV documentary Cinemassacre's Monster Madness (2007).

Betsy also appeared in the video documentary short A Friday the 13th Reunion in 2009. 2003's Freddy vs Jason featured Paula Shaw as Jason's mother. In the 8 minute fan film Voorhees (Born on a Friday) (2011), the role of Mrs. Voorhees was played by Monica DeNatale.

No matter her feelings about the film, the fans at I-Con who visited her table were enthusiastic. One fan even had her autograph his leg. The autograph was destined to become a tattoo.

My last contact with her was when she settled into the limo that would transport her back to her Manhattan Apartment. She leaned forward to say thanks and gave me a long goodbye kiss.

--Professor Kinema

Posted at 09:19 PM in Kinema Archives | Permalink | Comments (0)

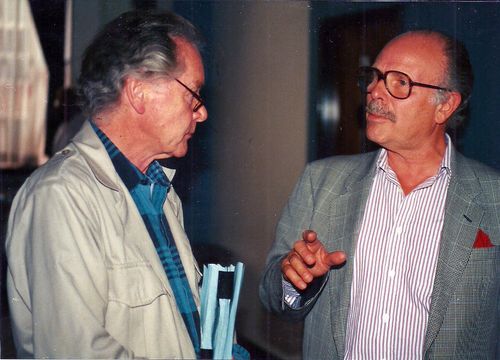

Edward Hardwicke and Jeremy Brett (photo by Jim Knusch)

Encounter with Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson

by Jim Knusch

In August of 1991 my girlfriend and travel companion, and I, were traveling abroad. Our itinerary for this particular trip was first a week in and around London, then on to a few other European locales. As a favor to some friends who were publishing a magazine named Scarlet Street, I agreed to get a few interviews. First up--the very afternoon of the day we arrived in London--were Jeremy Brett and Edward Hardwicke, Sherlock Holmes and Doctor Watson themselves.

Jeremy Brett started life as Peter Jeremy William Huggins. Because his father thought acting was a dubious profession he forbade him from using the family name on stage. So Jeremy took his stage name from the label of his first suit, 'Brett & Co.' On the screen he appeared with Audrey Hepburn in two major big budget films: as her brother Nikolai Rostov in War and Peace (1956), and later as her suitor Freddy Eynsford-Hill in My Fair Lady (1964).

Edward Hardwicke was from a totally different realm. He was born into a showbiz family, being the son of famed actor Sir Cedric Hardwicke. His first screen appearance was in 1943 in an unbilled appearance as a British Boy in A Guy Named Joe. At the time they were teamed as Holmes and Watson, Brett was just one year younger than Hardwicke.

With a portable cassette player, a notebook, and a 35mm camera in hand, I made my way to the Great Western Synagogue in London, where rehearsals for The Master Blackmailer were beginning. This wasn't 221B Baker Street (an actual address in London), but a certain thrill and magic for me were there just the same. My password for entry was Granada TV. I was brought into the room where the principal cast and director, Peter Hammond, were all seated at a table reading through the script. My host, who allowed me in, kindly told me to have a seat, pour a cup of tea, and be comfortable.

By this time, Granada TV had produced the series The Adventures of Sherlock Holmes which ran for 13 episodes (1984-85), The Return of Sherlock Holmes (1986-88), and two Sherlock Holmes TV movies: The Sign of Four (1987) and The Hound of the Baskervilles (1988). In between, Sherlock Holmes was turning up as part of the PBS Masterpiece Mystery (1987-88) in the USA. At the time of my interviews, the series was again in production by Granada as The Casebook of Sherlock Holmes (1991-93). The Master Blackmailer, based on the short story The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton, was to be a special two-hour episode. Being about the seventh of nine entries of the current series it was scheduled to air in England in January 1992.

Mixed into all of this was a theatrical adaptation, The Secret of Sherlock Holmes, by Jeremy Brett's friend, playwright Jeremy Paul. The production ran at Wyndham's Theatre in London's West End with Brett (as Holmes) and Edward Hardwicke (as Doctor Watson) during 1988 and 1989. The production subsequently toured. Research shows that it never made it to Broadway. If it did come to the USA, it must have had a limited touring schedule in select cities. Interestingly, Brett had previously played Doctor Watson on stage opposite Charlton Heston as Holmes in the 1980 Los Angeles production of The Crucifer of Blood, making him one of only four actors to play both Holmes and Watson professionally.

Since I had only occasionally caught an episode here and there of this now truly classic TV series, my friends at Scarlet Street magazine shipped VHS copies of all of the Sherlock Holmes shows they had available to the Kinema Archives. In the days before we planed off I managed to binge-watch them all (overdosing on them in the process) and jotted down many notes.

In the all-purpose room of the Great Western Synagogue the read-through was finished. I remember Mr. Brett saying something like, "Well, I guess that's it for today, except for our friend over here (pointing to me). Edward Hardwicke requested to be interviewed first, saying that he was dashing off to the theater. I managed to take a few photos, although, unfortunately, none with me posing with them. Eventually all departed, leaving me and Jeremy alone to have a nice, casual, interview and engage in light conversation.

My interview with Jeremy Brett

Has your approach to playing Sherlock Holmes changed over the years?

Brett: Yes, lots, insofar as I had to learn how to play him. Not that I've learned yet. But when I first started I was incredibly nervous about getting it wrong and I've relaxed a little bit.

You've been playing Sherlock Holmes for nine years now.

Brett: I started in '83 and I think I've learned a few things. Not many, but a few.

I presume you were aware of the stories and had formed an image in your mind of Sherlock Holmes?

Brett: Well I was very fortunate, because it was offered in '82 and then was cancelled. I went off to Canada to play Prospero in The Tempest and when I finished that, I had the Canon. So I had plenty of time to read. I'd read it when I was at school at university, but not as a part to play. So by the time Granada got back to me again, I was ready. I'm still aiming at the same thing, which is to get it right. It's much better read than to be actually seen.

Have you a favorite episode from the series?

Brett: I think the beginning of The Dancing Men, when I asked my director if I could actually lift it from the printed page. We realized we actually could do Doyle, undiluted. In that case, even unadapted. And that was exciting. Dangerous, but exciting. We were very low on confidence when we started, particularly me. Nobody really wanted to do it because everyone said it's been done. It was only after the first year and a half when we started to sell, I think, to 35 countries, that we began to take heart.

So this one particular episode struck a chord?

Brett: I began to think, my gosh, I might be able to play this part. The production standards, thanks to Granada Studios, have always been very, very high. And I've had two brilliant Watsons, which has been wonderful for me.

How would you compare David Burke and Edward Hardwicke as your two Watsons?

Brett: Well, they've very beautifully dovetailed each other. Quite remarkably, some people in Japan and now Russia have written saying how brilliant it was, the aging of Watson between The Final Problem and The Empty House. So, fortunately, thanks to the enormous tact of both of them - and David Burke's wife, who suggested Edward to take over, I've been very, very fortunate. You must remember the whole project was created by Michael Cox at Granada, to put posterity straight in regard to Watson. Thanks to those two marvelous actors, David Burke and Edward Hardwicke, It's been done.

Did your playing of Sherlock Holmes alter with the change in Watsons?

Brett: Oh yes, very much.

You're one of the few actors to play both Holmes and Watson. What was your approach to the character of the Doctor?

Brett: Well, I was fortunate being the son of a soldier. I have some military blood in my veins, I suppose. I played him with enormous enthusiasm and devotion to Holmes. With enormous respect although I got quite angry and upset--very upset--when Holmes abused himself. I would kill for him. That's how I played Watson.

Are there any predecessors in either role that you particularly admire?

Brett: I suppose my favorite one is James Mason; he's my favorite Watson. I guess my favorite Holmes will be Basil Rathbone forever. He seems to me to be the Paget drawings on the move--not having seen William Gillette, of course (laughs).

Have you ever seen Ellie Norwood as Holmes?

Brett: No, I haven't. I did start to see a few films before we started shooting, and I actually stopped because I got so overwhelmed and fearful. I thought, I really shouldn't be playing this part at all. So I stopped.

What was the most difficult episode to film?

Brett: Probably The Blue Carbuncle. That Sidney Pagent drawing is so marvelous, with Holmes lying sideways on the sofa. I had to actually be in that position for about a day and a half, so I could very nearly not stand up straight at the end of shooting the scene.

So it was physically, not mentally taxing?

Brett: It was an undiluted piece of brilliant deduction. And one so invariably gets it wrong. I remember thinking that was a particularly tough film.

Why did you decide to come back to Holmes with The Master Blackmailer, which is based on The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton?

Brett: Oh I rang up about March and said I was prepared to finish the Canon as long as they gave me gaps and took care of me.

I heard you were going to do three more.

Brett: No, we're finishing the Canon.

The entire Canon?

Brett: Last March I girded my loins and asked Granada what they'd say if I was willing to do it. They said you are our most successful series, you have our blessing. So I rang a very important person named Edward Hardwicke--we're joined at the hip--and asked if he'd come with me and the answer was yes. So we decided to go for the gold.

That's wonderful, but some of the short stories don't seem to lend themselves to screen adaptation.

Brett: They need a little help, yes, but we're getting better at that. We're kind of doing it in the Doylean way. For instance, The Adventure of Charles Augustus Milverton is one of his shortest stories. We've just completed a two-hour movie, and I think Dame Jean Conan Doyle read it and she's thrilled. I think we can do it if we're careful, but it's going to need a little work.

As a matter of fact, I read it too. In a roundabout way I did see a copy sent by Jeremy Paul.

Brett: You did? Were you pleased?

Very Pleased. It was wonderful.

Brett: What about Holmes being kissed when he becomes engaged to Milverton's maid, Agnes?

I think it all works beautifully.

Brett: Well I mean she kisses me. I don't do anything (laughs).

You've stated that you want the episodes to stay as faithful to the stories as possible.

Brett: That's true.

How is it possible with The Master Blackmailer, which was, as you said, a short story and has been given a two-hour format?

Brett: Blackmail seems to take that long. Luckily, Jeremy Paul, who did the play The Secret of Sherlock Holmes for me, which I commissioned in 1987, has done a fine job. The book is there, but it comes at the end.

Is there a possibility that you might be bringing the play to the USA?

Brett: Yes, in '94.

Any remarks about your other co-stars? Rosalie Williams and, on occasion, Colin Jeavons?

Brett: Well, my Lastrade, my darling Colin who's with me in this, and my darling Rosalie who's with me in The Master Blackmailer--I mean we've become family over the years. Every time Rosalie or Colin are in it I rejoice.

Have you been disappointed in any particular episode?

Brett: No. I haven't been too particularly thrilled, either. I think that maybe when you seek perfection you can't do anything else but fail. I feel I like little bits and pieces of me: 10 minutes, maybe, out of 32 hours. I'm not very good at looking at myself. I like it when I'm not speaking. What I can't believe is when I'm speaking. Sometimes when I'm doing physical things, I think, well, that's not bad. But I never feel like Holmes when I speak. I do when I'm doing it, but not when I see it.

George Bernard Holmes based Henry Higgins on Sherlock Holmes. Have you any desire to play Higgins?

Brett: No. I've just been offered Higgins.

Really? Perhaps there's a connection between them.

Brett: No, They're just two isolated men. I don't think there's any connection, really.

What are your immediate plans?

Brett: To complete this, have a gap, and then we'll see. I think they're preparing three already, for next year. And a further three, later, and we'll see how far we can go.

Thank you so much.

My interview with Edward Hardwicke

You come from an acting family. Were you encouraged to become an actor or discouraged?

Hardwicke: Well, they were very neutral about it. In think they were quite pleased, in a way. When I started it wasn't like today, when it's become such a fashion for acting families to continue. That certainly wasn't the case when I started.

Your father, Sir Cedric Hardwicke, once played Sherlock Holmes on radio, didn't he?

Hardwicke: Yes he did. I didn't even know that until a couple of years ago. Somebody sent me a tape of the vintage show that they somehow managed to get. I don't know how they got it, but I didn't realize that he had done that.

Was it difficult to step into David Burke's shows as Watson?

Hardwicke: In my mind it was difficult. It was made very easy by Granada and particularly by Jeremy and the team, the regular team of people who were putting the program on. They couldn't have been more helpful. Of course, there is a sort of physical image of these two characters. You think of Holmes in the black coat and Watson tends to have the bowler hat and the mustache, so in a sense you had all the guidelines, which helped.

What episode did you film first?

Hardwicke: The Abbey Grange, which was directed by Peter Hammond, who's doing The Master Blackmailer. That was the first one I did with them.

Do you see your Watson as being different from those of your predecessors?

Hardwicke: Well, inevitably it's different, because you're dealing with different actors. I think when you're dealing in film, you have to play very close to yourself. I don't mean to say that I'm remotely like Watson; I couldn't be a doctor to save my life (laughs).

That's a funny way of putting it. Not many people think of Dr. Watson as a professional man.

Hardwicke: Well, I do; that's a very important part of him. Being a detective is very much like being a doctor. Somebody comes to you in pain and asks what's wrong with me and you have to tell them. I think there's a huge similarity, and this analytical side of Holmes' detection appeals to Watson.

Roger Hammond (Jabez Wilson) and Edward Hardwicke

Roger Hammond (Jabez Wilson) and Edward Hardwicke

(photo by Jim Knusch)

Do you find yourself mimicking any previous Watsons?

Hardwicke: Not at all, no. I remember once in the National Theatre with Lawrence Olivier, when I took over a part in a play, Olivier's advice was "Pinch any bit of business that you like. I always have done that." And I think that's part of the theater tradition. The tradition of English acting is based on other actors, rather than people; I think it's a kind of house style, if you like.

Have you a favorite episode?

Hardwicke: No. There are two ways of looking at anything you do on film. The actual circumstances in which you film it, that is to say the cast and whether you get on with them, whether you have friends, and the conditions in which the film is made, the actual stories. If you read the stories I suppose one inevitably goes to the famous ones, which I was not involved in, like The Speckled Band. Of the ones we've done one is colored by the circumstances in which they were filmed. I've enjoyed a lot of them hugely. I mean there've been a number of great friends who've played parts, and that's given it a kind of enjoyment which is very special.

Is there an episode that didn't come off quite as you wanted it to?

Hardwicke: Well I think it would be impossible to say that any of them came off quite as I wanted them. That's difficult, again. I'm not dodging the question, but you have personal disappointments in things that you feel you would have liked to achieve in a particular episode. This is always true of acting; it's one of the penalties of seeing things on film. I always avoid going to rushes. Jeremy likes to do it, but I think that every actor has a different way of approaching these things. I don't go because I find that I'm always disappointed; I think I've done something and something quite different appears, but it may be the difference that's the interesting thing that you do. To go back to the question, yes, there are lots of moments when I felt that I haven't done what was in my head to do, and that's always a disappointment.

What's your opinion of The Hound of the Baskervilles, in which you had more screen time than Jeremy Brett?

Hardwicke: Well, that's the nature of the story, the way Doyle wrote it. The great thing is that Holmes lurks menacingly, if you like, to put it that way, throughout the whole story. Although you don't see him, one has the suspicion that he's around, which of course he is.

What's your overall opinion of The Hound?

Hardwicke: I think that's a great story. I suppose if one had to be pinned to a wall, that's the story most people associate with Sherlock Holmes. It's a terrific story, very difficult to put on film; I don't think we succeeded entirely with that one, but then I don't think you can. You're up against people's imaginations. You're dealing with a book, and people read it and every person who reads it has his own idea, so you're competing with millions of different versions of the same thing. You can't hope to please everybody.

Did you play Watson differently on stage in The Secret of Sherlock Holmes than you play him on film?

Hardwicke: Not consciously. I think you work the material you're provided with, really. The play was an interesting idea, and dealt very much with the relationship between the two men, and what happened when Holmes disappeared and the effect it had on Watson. And to that extent you play that. You pick up a script, you read it. You see how you can make that work.

In television, a weak performance can be made to look better through editing, and vice versa.

Hardwicke: Oh sure, sure.

And a powerful performance can be diluted by the way it's presented on the screen.

Hardwicke: Yes, that's absolutely right. You are, in the theater, your own master. Nobody is pulling the strings.

If Jeremy Brett is willing to continue with the series, are you?

Hardwicke: Well, at the moment, I don't know what will happen. We're doing this particular one. We thought--this was sort of a surprise, and a delightful one--we thought we'd finished. And then they decided to do this two hour special, which we are enjoying enormously. Beyond that, I really don't know.

I heard they're preparing at least three more.

Hardwicke: They've got to settle the question of television licenses and such.

One of the nice things about the series is the rapport that Watson has with Inspector Lestrade, particularly in The Empty House and The Six Napoleons. Did you work this out with Colin Jeavons or was it part of the script?

Hardwicke: Well it's very nice that you should have picked that up. It never occurred to me. I think that, if it's there, it was in the script, and we must have just found that and that's what happened. I think that probably is the case; certainly, in The Empty House, I remember we had quite a few scenes. In the end it's a question of whether you have scenes together: a relationship will develop of some sort.

What, besides The Secret of Sherlock Holmes have you been doing in the theater lately?

Hardwicke: I've done a little directing over the last couple of years, which I've enjoyed hugely. I would love to go back to do something on the theater, some farce or some comic stuff, which is my particular favorite. Beyond doing The Master Blackmailer I have no particular plans of any sort.

Thank you immensely. It's been a pleasure.

Ultimately another season of Sherlock Holmes Adventures was produced by Granada called The Memoirs of Sherlock Holmes (1994). The final episode featuring Jeremy Brett and Edward Hardwicke was The Cardboard Box.

Jeremy Brett wound up his 40 year career appearing in two films: Mad Dogs and Englishmen (1995) and Moll Flanders (1996). He passed away at age 61 in 1995 of iatrogenic congestive cardiac failure. Edward Hardwicke appeared as Sir Arthur Conan Doyle in a film released in 1997 titled Photographing Fairies. He appeared in one episode of Agatha Christie's Poirot television series as Sir Henry Angkatell titled The Hollow (2004). He wound up his almost 70 year career with a film appearance as Mr. Brownlow in Roman Polanski's Oliver Twist (2005). He passed away at age 71 in 2011 from cancer.

Posted at 10:40 AM in Kinema Archives | Permalink | Comments (0)

By Jim Knüsch (Professor Kinema)

In the early 1990s I had researched background information for an article on the film Burn, Witch, Burn, which was to appear in FilmFax magazine. During my research I borrowed a 16mm print of the movie from film historian William K Everson. Everson and I got to talking about the specifics of the film and he suggested I get in touch with one of its screenwriters, George Baxt, who was, at the time, living in New York. His number was listed in the phone book. I called him and made an appointment to interview him. During two visits and a few follow-up phone calls we talked not only about Burn, Witch, Burn, but also touched upon the other genre films he was involved with. The article I eventually wrote regarding Burn, Witch, Burn ended up in Scarlet Street magazine instead of FilmFax.

My interview with this Edgar Award winning author turned into more of a general rap session where he shared his interesting insights and recollections for Circus of Horrors, Burn, Witch, Burn, Vampire Circus, The City of the Dead, and Shadow of the Cat. Within this article I’ve arranged Baxt’s insights and recollections according to each relevant movie discussed.

Posted at 05:18 PM in Kinema Archives, Reflections | Permalink | Comments (0)

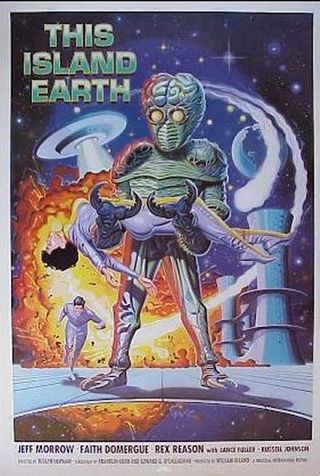

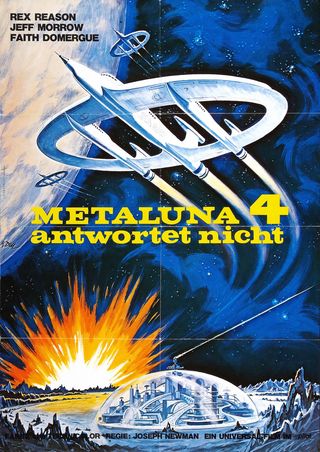

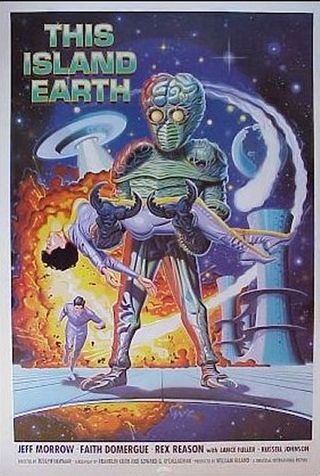

This interview, conducted by Professor Kinema (Jim Knusch) with actor Jeff Morrow, originally appeared in Psychotronic Video magazine (Fall, 1993). Professor Kinema expands on his article for Zombos' Closet. Photos and illustrations are from Professor Kinema's archives.

Jim: The second movie on your Universal contract was Captain Lightfoot.

Jeff: Yes, that was shot on location, being set on a little Irish seacoast town. In the appropriate roles local actors were utilized. I played a pleasant Roman gentleman. The one element of working on location I remember was the sight of the poor Irish children I observed early in the morning picking through the garbage. However, all involved made it a pleasant experience.

Jeff Morrow next appeared in World in My Corner (1956) with Audie Murphy and The First Texan (1956) with Joel McCrea playing Sam Houston. Pardners (1956) came next. This ironically titled film featured Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis who were to make one more feature, Hollywood or Bust, before breaking up completely.

Jim: Was it, sort of, a solid rumor that Martin and Lewis were on the road to breaking as a team during the making of Pardners?"

Jeff: Yes, I believe so. I remember Jerry Lewis would occasionally go a little wacky on the set, in front of and behind the camera. He had a habit of trying to distract off-camera. In Pardners I had a bar room fight scene. I remember Jerry Lewis being knocked into a dark closet and suddenly emerging an excellent fighter (as Dean Martin).

Jim: Also that year, 1956, came the third Creature film, The Creature Walks Among Us. This was the last of the series, the only one not filmed in 3D. Also, it was the only film in the series in which the creature doesn't die at the end.

Jeff: Yes, that's right. I hadn't seen the previous two Creature films but I was aware of them. My Universal contract was still in effect and there wasn't another film property that they could use me in at the time. It wasn't a bad script and I made the most of it.

Jim: Significantly, you were teamed with This Island Earth co-star Rex Reason. Do you have any recollections of any of the others in the cast?

Jeff: Leigh Snowden, I thought, was a beautiful ingénue. I remember there were both Ricou Browning and Don Megowen as the Creature, in and out of the water.

Jim: Yes, I believe that was the case in the first two Creature films. In the water the Creature moved with a balletic grace as he glided through the clear waters of the Black Lagoon. Once he is confronted on land it takes on the personality of the lumbering beast.

Jeff: I thought the Creature costume, both before and after the burning incident, was convincing. There was a scene that takes place on a balcony where I was being pursued by the Creature. He picks me up to toss me over. In the final cut a dummy goes over, yet for a moment before the director yelled "Cut!" I thought I was going over for real.

Jim: Were there any locations other than the back lot used during production?

Jeff: No, we never left Hollywood. I remember the scene where the Creature was set on fire was shot on one particular night when we were working quite late.

Jim: The next year, 1957, you appeared in two sci-fi- films,Kronos and The Giant Claw. Both films were produced on low budgets, both were concerned with a giant alien menace who possessed a powerful other-worldly power. Kronos, however, was relatively well made and possessed a sound scientific premise while The Giant Claw is generally regarded as one of the prime turkeys of the 1950s.

Jeff: (Laughing) Yes, that's unfortunately true. The Giant Claw seemed to initially have a sensible premise as well as a good storyline. The concept of antimatter was a plausible scientific theory at the time and attempting to depict it on the screen wasn't far beyond the realm of believability. We were told that the giant bird was supposed to be a sort of streamlined hawk that could travel at supersonic speeds. We weren't shown any sketches of it. The first time I saw the film I was in a theater with friends, I believe, in Westwood. During the screening all was going well until that big bird first appeared on the screen. The audience was howling. Every time it reappeared I just sank lower and lower into my seat. Whenever I attended a film that I appeared in with family and friends it was customary to gather in the lobby and discuss it afterwards. In the case of The Giant Claw I couldn't face anyone and discretely slipped out one of the rear exits.

Jim: Well, I'm sure that no one in attendance thought that you, the star of the film, was responsible for the less than stellar special effects?

Jeff: No, no one did, but still it was embarrassing.

Jim: Yet films like The Giant Claw prove to be as fondly remembered as the larger and more prestigious productions like This Island Earth.

Jeff: Yes, I believe so. At the time we hoped that such films like The Giant Claw would run their course and quietly fade into oblivion, never to be seen again.

Jim: Well, and I say this as an aficionado of bad films, fortunately they do surface and find new audiences who view and even cherish them with different sensibilities. Do you have any memories of Kronos ?

Jeff: Yes, I believe we worked on that for about four weeks. Again, because of the limited budget, the special effects couldn't live up to the potentials of the premise of the story.

Jim: Yet, visuals of a gigantic rampaging simplistically designed automaton from outer space was easier to ingest than a gigantic buzzard from outer space - with flaring nostrils, no less. However, one interesting fact is that the story of Kronos was concocted by special effects artists Irving Block and Jack Rabin. Block worked on Forbidden Planet (1956) and the team worked on films like The Invisible Boy, Roger Corman's Viking Women and the Sea Serpent, War of the Satellites, and The Thirty Foot Bride of Candy Rock, Lou Costello's final film.

Jeff: Anyway, with Kronos I wasn't compelled to quietly slink out of the back door of a movie theater after my initial viewing of it. I enjoyed working with Kurt Neuman, co-players Barbara Lawrence, George O'Hanlon, and Morris Ankrum. I had worked with Morris on The Giant Claw and found him...being old. John Emery was an old friend. We both appeared in a New York stage production of Saint Joan.

Jeff Morrow's next several screen appearances ranged from big budget large screen productions like The Story of Ruth (1960) (reuniting him with The Robe director Henry Kosher) and smaller productions like Harbor Lights (1963) (in which the title doesn't have the remotest connection with the story.). Also appearing on television he helped build Union Pacific (as star of the series), was in residency in The New Temperature's Rising, and guested on several other major series. In Rod Serling's The Twilight Zone he appeared in a memorable episode titled Elegy (written by Charles Beaumont and aired 2/19/60). In it he is one of three astronauts who find themselves on a strange planet where people are frozen amidst various settings. They eventually meet a kindly old gentleman who turns out to be the caretaker of what they find out--too late--that the planet is a cemetery.

Jim: Do you have any memories of The Twilight Zone episode, Elegy?

Jeff: Like it was, working in virtually all television production of the time, the shooting schedule was rushed. My co-stars were Don Dubbins, Kevin Hagen and Cecil Kellaway. What I remember most about Cecil was of him being sly. When he was off camera he was always doing something to distract whoever was on camera. Also, when he was in a scene with other performers he was busy doing some sort of business so that he would dominate the action in the scene.

Jim: Do you have any memories of Rod Serling?

Jeff: He was a real friendly and talented person. He wasn't too actively connected with Elegy while it was being shot. We were all genuinely saddened when he died so young.

Jim: Now the last two film titles I have to ask you about are Legacy of Blood from 1971 and Octaman from 1973.

Jeff: Like The Giant Claw and Copper Sky earlier in my career, my agent tells me to do it, Legacy of Blood, take the money and run. No one will see it and it should be quickly forgotten. The only significant element of Legacy of Blood would be is that I was reunited with Faith Domergue. I don't consider it one of my better efforts at all. On bad nights I would probably have a nightmare about it. With Octaman I was a friend of the screenwriter, Leigh Chapman, and the director, Harry Essex (a writer of the first Creature film) who asked me as a personal favor to appear in what amounted to little more than a cameo. I worked for three days and was in a short scene with Kerwin Mathews. The other leading player was Pier Angeli, who committed suicide during production, I believe.

Jim: For the record, the official reason for her taking her own life was that she couldn't face life after the age of 40. Did you encounter the young Rick Baker who created the Octaman at all?

Jeff: I had little to do with him in the three days I worked on the picture. I remember Octaman looking a bit on the silly side. It's fortunate, though, that Rick continued to persevere and go on to create some fabulous makeups and win awards.

Jim: Do you stay in touch with any of the people that you've worked with? What of Rex Reason and Faith Domergue?

Jeff: No, I haven't been in touch with Rex and Faith in recent years. Rex, I believe, went into real estate. He had stayed active in TV doing guest shots in various series and commercials for a while. His brother Rhodes Reason I know stayed professionally active. Faith? I lost contact with her. The last I heard was that she was moving to Italy.

Faith Domergue did in fact live and make a few films in Italy in the 1960s and 1970s. She passed away on April 4 1999 in Santa Barbara, age 74.

Jim: Have you saved much from the old days?

Jeff: I have photos. When you work on the stage and in movies you have many photos that have been made up for promotion and publicity purposes. I also have many posters. Unfortunately I don't have the wall space to display them.

Jim: You've also had a career as a commercial artist?

Jeff: About 95 percent of all who work as a performer have some sort of back up work that pays the bills in between acting jobs. I've done illustrations for magazines, technical drawings, organizational charts, progressive charts, flow charts. That kind of work.

Jim: In the MagicImage Filmbook of This Island Earth there is an excellent rendering of yourself as Exeter by you. What have you been doing these days?

Jeff: My wife, Anna Karen, who was an actress, started a real estate business about eight or nine years ago. Being a member of the Academy [of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences] we attend many screenings of current films throughout the year and generally stay in with the film folk.

Jeff Morrow passed away Dec 26, 1993 in his home in Canoga park at the age of 86.

Posted at 02:32 PM in Kinema Archives | Permalink | Comments (0)

This interview, conducted by Professor Kinema (Jim Knusch) with actor Jeff Morrow, originally appeared in Psychotronic Video magazine (Fall, 1993). Professor Kinema expands on his article for Zombos' Closet. Photos and illustrations are from Professor Kinema's archives.

This Island Earth (1955), a major studio-produced true science fiction epic, has been described as "a Science Fiction pulp cover brought to life." Screen immortality was achieved with the appearance of Exeter, emissary from a planet in a distant galaxy called Petaluma. In appearance he stood tall and gaunt topped with a high forehead sporting a crop of puffy white hair. Curiously, none of the other resident Earthly geniuses under his tutelage questions or even seemed to notice these physical eccentricities. Two characters take the time and effort to render two accurate portrait drawings of Exeter and his assistant Brack and comment only on their forehead recesses.

Yet this alien, under orders from a beaten and desperate exterrestrial governmental force exude a dignity and humanness rare in science fiction films of any era. These qualities, absorbed from living among Earthlings, proved to be his fatal undoing, while at the same time the saving grace of the two protagonists. While most cinematic visitors from the Cosmos come here to conquer, issue some sort of ultimatum for peace, or in some way do grievous harm, Exeter emerged as the true hero of This Island Earth. This unique quality was infused in this character by the actor, the very Earthbound Jeff Morrow. Perhaps the only other movie alien in the very Earthbound science fiction cinema that was more prominent on the screen than Exeter was Michael Rennie's Klaatu from the original The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951).

Yet this alien, under orders from a beaten and desperate exterrestrial governmental force exude a dignity and humanness rare in science fiction films of any era. These qualities, absorbed from living among Earthlings, proved to be his fatal undoing, while at the same time the saving grace of the two protagonists. While most cinematic visitors from the Cosmos come here to conquer, issue some sort of ultimatum for peace, or in some way do grievous harm, Exeter emerged as the true hero of This Island Earth. This unique quality was infused in this character by the actor, the very Earthbound Jeff Morrow. Perhaps the only other movie alien in the very Earthbound science fiction cinema that was more prominent on the screen than Exeter was Michael Rennie's Klaatu from the original The Day the Earth Stood Still (1951).

In the history of science fiction films, mainly those with aliens from other worlds, the aliens are almost always depicted as strangely shaped humans. Some are completely humanoid in appearance (as if to enhance Van Dannikan's theory that all life in the universe spawned from a common ancestor), partially humanoid, or grotesquely shaped. However, they all seem to be able to function in Earth's environment, breath our air, and, in the case of The Thing From Another World, thrive on the blood of Earthlings. Most even speak our lingo, mainly English.

More recently, the film Avatar utilized advanced CGI to depict aliens as well as humans morphed into aliens. But again, all seemed to be infused with very human personalities adorned with long blue bodies and tails. Two films stand out as examples of depiction that were convincingly alien (at least to me): The Andromeda Strain (1971) and 2001, A Space Odyssey (1968).

The former film presented a life entity that took the form of a virus that became very deadly when exposed to Earth's atmosphere. However, like a true virus (albeit, Earth born virus), it mutated into something benign. In the Stanley Kubrick opus, the aliens were presented in the very last scenes. Over the actions of the hapless space traveler (Kier Dullea) in the elaborate room is heard their voices, presumably commenting on the action and humanity's future (or demise).

Other 1950s aliens that come to mind are those in War of the World's, The Man From Planet X, The Phantom From Space, The Devil Girl From Mars, the pop-eyed Killers From Space, the Venusian mushroom creature of It Conquered the World, the alien vampire of Not of This Earth, Eros and Tanna (plus, of course, the Ruler) of Plan 9 From Outer Space, and the long dead and never seen Krell of Forbidden Planet.

The list could definitely go on. The bulk of this alien invasion population had far less than kind intentions for Earthlings. Morrow's Exeter character was presented as being assigned to systematically kidnap Earth scientists expressly for his home planet's needs. Evidently, his far advanced planet thrives on the identical science and technologies that can be found on Earth.

His acquired alien-humanness surfaced at the point in the film's story when he defies the supreme ruler's direct order to subject Rex Reason's and Faith Domergue's characters to the brain transformer (an other-worldly lobotomy) device. As they make their escape from the doomed planet, Exeter's ship uses up all its rocket fuel (no similar fuel could be found or somehow manufactured on Earth?) returning them to Earth. With nowhere else to go, no fuel, and no one of his race left, Exeter commits suicide by crashing his ship into the ocean.

In a case where an actor's persona infuses with his on-screen character's and creates a truly memorable performance, such is Jeff Morrow's contribution to This Island Earth.

Jim: Now we come to This Island Earth.

Jeff: I had just signed a contract with Universal for two pictures a year. I was offered the role of Exeter and read the script. I liked the story very much and thought that the Exeter character had much potential...with a few changes. My contract didn't start for a few weeks so I was under no obligation to accept the role. I had a conference with the screenwriter, Franklyn Coen, and suggested the changes in the character. The producer, Bill Alland, then got in on the conference.

Jim: Would you recall what the changes were?

Jeff: Exeter as written was more of a two-dimensional character. By the end of the story he emerged a sort of self-sacrificing tragic hero. Specific points of the script that were revised I can't recall but had to be concerned with Exeter as a scientist, his dedication to his home planet and civilization, and ultimate realization of the futility of it all.

Jim: This would contrast with the Brack and Monitor characters. Both of them were coldly dedicated to the mission and seemed to not care about any of the Earth scientists, or even for the entire Earth population for that matter.

Jeff: Yes, that's right. These subtle script changes were shown to the front office and they unanimously approved them. Franklyn Coen made the comment, "Great! I've been trying to sell them on similar changes for the past several months."

Jim: There is one line in the script that was spoken by you (as the Exeter character) toward the end of the film that I believe will be remembered as the immortal line of This Island Earth. You, Faith Domergue, and Rex Reason are confronted by an injured Metalunian mutant, which stands about 7 feet tall. They ask, "What is it?" You answer, "...actually they are quite similar to the insect life on your planet...larger of course, with a higher degree of intelligence."

Jim: There is one line in the script that was spoken by you (as the Exeter character) toward the end of the film that I believe will be remembered as the immortal line of This Island Earth. You, Faith Domergue, and Rex Reason are confronted by an injured Metalunian mutant, which stands about 7 feet tall. They ask, "What is it?" You answer, "...actually they are quite similar to the insect life on your planet...larger of course, with a higher degree of intelligence."

Jeff: Yes, (laughs) that's right.

We both shared a laugh at this point.

Jim: Do you remember how long your involvement with This Island Earth was?

Jeff: Yes, four, maybe six weeks. I remember six day weeks and long tedious days. I had to be at the studio at 6am to be made up and on the set by at least 8am.

Jim: So presumably the "2 and 1/2 years in the making" that figured in the film's promotion was taken up by elaborate set building, miniature set building, special makeup, costumes, and the highly impressive special visual effects. Do you recall any of the set-ups of any special effects scenes that involved you?

Jeff: I do remember being in front of a sort of process screen gesturing to off-screen actions.

Jim: It has been established that Jack Arnold was involved in the latter part of This Island Earth. Do you recall working with him?

Jeff: What I do recall is that Jack was originally scheduled to direct This Island Earth but, I believe, was pulled off the project and assigned to something else. Joseph Newman handled the bulk of the direction. I do remember Jack at work during the sequences that took place on Metaluna.

Jim: This was because Newman's footage proved to be inadequate so Arnold was recalled to reshoot it, being a director who could more effectively handle aliens, BEMs, an intergalactic war and a fiery return by a UFO to Earth.

Jeff: Yes, that's true.

Reportedly, the budget for This Island Earth was something like $800,000, a hefty sum for any studio in the early 1950s. In modern times such a property would run up a bill in the tens of millions. Universal had the advantage of having personnel on salary and owning the facilities used.

Reportedly, the budget for This Island Earth was something like $800,000, a hefty sum for any studio in the early 1950s. In modern times such a property would run up a bill in the tens of millions. Universal had the advantage of having personnel on salary and owning the facilities used.

One of the largest material costs was the mutant suit at $20,000. People who worked on the suit were Jack Kevan, Robert Hickman, Chris Mueller and Millicent Patrick. The creature was first played by Eddie Parker, who left after a salary dispute, and then Regis Parton. Parton is listed in the credits.

The suit is generally well designed with a few glitches. The face is almost totally immobile drawing attention to the fact that it is a full head mask. The pants are eccentric. Censorship laws of the day were such that even a creature from outer space couldn't be caught on screen without pants. The belt buckle has an atomic symbol on it and, most strange, the bottom of the pants become the mutant's feet. An alien being wearing only extraterrestrial-style pants also turns up in I Married a Monster From Outer Space (1958). The mutant's arms telescope into a section extending out further than a man's would. Unfortunately, they flop around loosely. One can only wonder what kind of menial work they were bred for (according to the story).

Jim: Do you have any memories of working with your co-stars: Rex Reason, Faith Domergue, Russell Johnson, and Douglas Spencer?

Jeff: They were all pleasant to work with. I know Faith hadn't made many films beyond the '6os. Rex, I know, continued in films for a while and, like myself, did TV shows and commercials. Russell Johnson, I know, continued an association with Jack Arnold which rolled into TV's Gilligan's Island.

Jim: You were reunited with Faith and Rex in later movies?

Jeff: Right. Rex I worked with again in The Creature Walks Among Us the following year. Faith I worked with again in 1973 in Legacy of Blood.

Jim: It's interesting to note that to further add to the feel of 1950s cinema sci-fi, two of the actors who appeared in This Island Earth had also been in The Thing From Another World. These two were Douglas Spenser and Robert Nichols.

Jeff: Yes, I didn't realize that.

Continue reading "Professor Kinema: The Jeff Morrow Interview

Part 3" »

Posted at 02:45 PM in Kinema Archives | Permalink | Comments (0)

This interview conducted by Professor Kinema (Jim Knusch) with actor Jeff Morrow originally appeared in Psychotronic Video magazine (Fall, 1993). Professor Kinema expands on his article for Zombos' Closet.

Jeff Morrow's film career began with the substantial role of Paulus, a Roman centurian, in the 20th Century Fox CinemaScope epic The Robe in 1953. He introduces Richard Burton to the Roman outpost in Jerusalem, calling it "the worst slime hole in the Empire." He is also one of the soldiers who casts lots for Jesus's robe, and he eventually has a sword fight with the star.

The Robe was the first Fox production to be released with the label In CinemaScope (also Technicolor and 4-track stereo). Various wide screen techniques had been experimented with since the early days of cinema. CinemaScope was Fox's trade name for an anamorphic wide screen process based on Henri Chretien's 1926 Anamorphoscope, which used an optical system called Hypergonar. A few early Fox films utilized what was then called Fox Grandeur, a 70mm anamorphic process. 1929's Fox Movietone Follies was one of them. According to Guinness Film Facts and Feats by Patrick Robertson, although Follies was lensed in 70mm Fox Grandeur, it was released in conventional frame format. John Wayne's The Big Trail (1930), and Happy Days (1930), Betty Grable's first screen appearance, were also released in Fox Grandeur wide screen.

Very few studios had experimented with wide screen formats. At the time, since there really wasn't a financially sound reason to continue with the added expense of filming in wide screen, experimentation stopped as normal screen dimensions were deemed adequate. In the early 1950s the threat of television began reducing theater attendance and Fox execs took the wide screen format off the shelf, dusted it off, and re-introduced it in an effort to lure movie-goers from their living rooms back into the theater.

The first 20th Century Fox production to actually finish production in CinemaScope (and also Technicolor and 4-track sound) was How to Marry a Millionaire. However, it was decided that instead of displaying the ample physical dimensions of Marilyn Monroe, Betty Grable, and Lauren Bacall in this new process, a more down to earth--and family friendly--biblical story was chosen instead to highlight it. The Robe had its very publicized world premier at the Roxy Theater in NYC on September 16, 1953. Formal dress was required. Two personalized tickets, a theater program and souvenir booklet for the event are in the Kinema Archives (one of these tickets is shown at the beginning of this article). The Robe was the first CinemaScope production to be nominated for an Oscar, but lost out to From Here to Eternity. Fox was so sure The Robe would be a hit they started filming the sequel, Demetrious and the Gladiators (with Victor Mature, Michael Rennie, and Jay Robinson) before post production of The Robe was completed.

The Jeff Morrow Interview (continued)

PK: What are your recollections of working on The Robe and those you worked with in front of as well as behind the camera?

Jeff: I was required to have a 5-day unshaven beard and wear bulky armor. Henry Koster, the director, was pleasant to work with. I admired Richard Burton as an actor. He also had extensive stage experience. Of the scenes I had with him I mostly remember the sword fight. Wearing bulky armor naturally made it difficult. I felt that it was lively and well done.

PK: And it did get notice?

Jeff: Yes, that's right.

PK: What are your recollections of working in CinemaScope?

Jeff: The decision to shoot in CinemaScope happened after the casting and costume fitting. Consequently, to make the necessary changeovers in set design, lighting, and in other technical areas, it caused a delay of three weeks. Of course, we all stayed on salary, since actors were paid that way in those years with very few exceptions. The schedule stretched to 10 to 11 weeks of shooting. Being in what was the premier wide screen production (also in Technicolor as well as 4-track stereo) generated much excitement in all of us. Even though I was coming to Hollywood from the stage, I was aware that the individual setups did take a bit longer than they would have taken. We were all aware of the fact that The Robe would cause a lot of attention for those who were appearing in it.

To me the outstanding character was Jay Robinson as Caligula. I'll never forget him. Yes, he acted eccentrically. One day while having lunch in the studio commisary, Jay went to a table that he had been sitting at for several days. This day, one of the 20th Century Fox studio execs was sitting in what he considered his seat. Well, Jay, in his costume as Caligula, ranted and raved about him sitting there. He made such a fuss and caused a totally stunned movie exec to move to another table. The exec could not believe that someone would dare shout orders at him. In this case, it was a Roman emperor.

Posted at 09:30 AM in Kinema Archives | Permalink | Comments (0)

This interview conducted by Professor Kinema (Jim Knusch) with actor Jeff Morrow originally appeared in Psychotronic Video magazine (Fall, 1993). Professor Kinema expands on his article for Zombos' Closet.

While most cinematic alien visitors from the Cosmos pay us a visit to conquer Earth, issue some sort of ultimatum for peace, or in some way threaten to do us harm, Exeter, instead emerged as a true hero in This Island Earth. His uniquely altruistic qualities were infused into his character by the very earthbound actor Jeff Morrow.

Morrow was originally from New York City where he was born Leslie Irving Morrow in 1913. He went to Pratt Institute and worked as a commercial illustrator to pay for drama school. He started acting on stage, in Pennsylvania, as early as 1927, and made his Broadway debut under the name Irving Morrow in 1936's Romeo and Juliet (he played Tybalt).

His other 23 stage roles were for Billy Budd, Across the Board, Three Wishes For Jamie, Candida, MacBeth (as Banquo with Maurice Evans and Judith Anderson), Saint Joan (with Kronos co-star John Emery), Lady From the Sea, What a Life, Penal Law, Once in a Lifetime, A Midsummer Night's Dream, and Twelfth Night. He shared the limelight with Dennis King, Eddie Bracken, Edith Evans, Katharine Cornell, Katharine Hepburn, Luise Rainer, Mae West, Torin Thatcher, Eli Wallach, Ralph Richardson, Basil Rathbone, Brian Ahern, and many others.

According to the souvenir booklet for The Robe, Morrow had appeared in 200 TV shows as well as being heard on 2000 radio programs before he made the journey to Hollywood. For two years he was heard as the voice of Dick Tracy. In all, he appeared in 23 films. Some were memorable like Flight to Tangiers, The Sign of the Pagan, Tanganyika, and Hour of Decision; and a few that, in his words, were "best forgotten:" The Siege at Red River, Copper Sky, Harbor Lights. There was one comedy, Pardners (with Dean Martin and Jerry Lewis).

Of special interest to science fiction fans are the select genre films he appeared in like This Island Earth, Kronos, The Creature Walks Among Us, and the not so memorable The Giant Claw, Legacy of Blood, and Octaman. On the small screen he starred in Union Pacific, appeared as a regular on The New Temperatures Rising, had notable roles on Daniel Boone, The Name of the Game, Perry Mason, The Virginian, Judd For the Defense, Sarge, Iron Horse, Wagon Train, Bonanza, GE Theater, Philco, Studio One, one very memorable episode of original Twilight Zone and another on the later revival of The Twilight Zone.

At the time of this interview (early 1993) he resided in Encino, California with his wife, former actress Anna Karen. His daughter, Lissa Megan Morrow, was a free-lance sportswriter. In these latter years he worked as a commercial illustrator while taking occasional acting assignments. To occupy in-between time he and his wife dabbled in Real Estate. After one introductory phone call we spoke for 90 minutes. The entire interview was recorded on an audiocassette which is now in the Kinema Archives. Afterwards I sent photographs to him, from my collection, for his autograph. When the envelope returned, a few extras from his own collection were included among them.

A transcript of the highlights of this interview, plus an article embellishment, was submitted to Mike Weldon, editor of Psychotronic Video magazine. After its publication, Jeff Morrow passed away, on December 26, 1993. Mike Weldon and I determined that this was the last interview Jeff Morrow did before he his death.

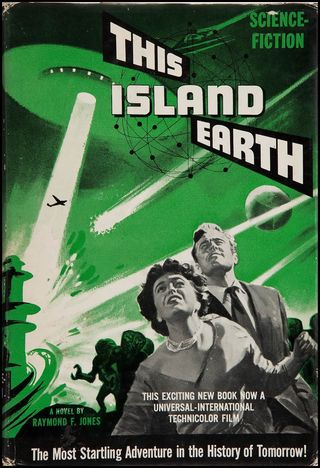

The article was received well by readers of Psychotronic Video magazine, with one minor exception: Bill "Keep Watching the Skies" Warren sent in a letter with a small detail he considered important enough to mention. In the article, regarding This Island Earth, I said how the original story developed from 3 stories originally published in 3 issues of Thrilling Wonder Stories, and how they morphed into a novelization for This Island Earth. Warren disagreed, and stated that what resulted was not a novelization. Mr. Warren is incorrect in his assessment.

The article was received well by readers of Psychotronic Video magazine, with one minor exception: Bill "Keep Watching the Skies" Warren sent in a letter with a small detail he considered important enough to mention. In the article, regarding This Island Earth, I said how the original story developed from 3 stories originally published in 3 issues of Thrilling Wonder Stories, and how they morphed into a novelization for This Island Earth. Warren disagreed, and stated that what resulted was not a novelization. Mr. Warren is incorrect in his assessment.

In the This Island Earth Universal Filmscripts Series there is an essay by Forrest J. Ackerman titled I Never Met a Luna Mutant I Didn't Like. In it he states how he was the literary agent for Raymond F. Jones and how he was involved with the publication of the novel of This Island Earth, which combined the three pulp stories. He goes on to mention that a publisher in Germany published the novelization (Ackerman's term) by Walter Ernsting.

The entry on Wikipedia concerning the This Island Earth novel contains the publishing history, listing four editions in all: the first novel was published in 1952; the German paperback edition in 1956 (the year after the release of the film); and two more paperback editions were published in 1991 and 1999. The 1999 version is a Forrest J. Ackerman Presents paperback reprinting the 1952 novel. An illustration of Jeff Morrow as Exeter adorns the cover. On the Amazon webpage, where copies of this book are offered for sale, readers comment on the original novel. It is referred to as a novelization.

At the end of his reworked entry on This Island Earth, in his 21st edition of Keep Watching the Skies, Warren states that the first published novel is a "fixup" (his term) of the three Raymond F. Jones stories. I am not sure what he means by "fixup." I have not seen any research into the history of published works where the term "fixup" is used in this regard.

At the end of his reworked entry on This Island Earth, in his 21st edition of Keep Watching the Skies, Warren states that the first published novel is a "fixup" (his term) of the three Raymond F. Jones stories. I am not sure what he means by "fixup." I have not seen any research into the history of published works where the term "fixup" is used in this regard.

So, I'll just say that my reworked and expanded articles on Jeff Morrow that will be appearing here are "fixups" and call it a day.

The Jeff Morrow Interview Conducted by Professor Kinema

PK: I must mention the fact that I am pleased to be conducting an interview with possibly the second most famous movie alien of the Fantastic Cinema of the 1950s. Exeter of This Island Earth ranks right up there next to Michael Rennie's Klaatu of The Day the Earth Stood Still. If there was ever an Alien Hall of Fame your Exeter would definitely be part of it.

Jeff: (laughs) Well, I'm flattered. I didn't realize that. I know of all the fan mail that I've received, the bulk of it has been from those remembering This Island Earth.

PK: Just as a matter of record, in Forrest J. Ackerman's Spacemen magazine, Exeter was paid a tribute of sorts. In issue #5 (October 1962) he was declared 'Spaceman of Distinction #2'. I believe that this was the only movie alien so mentioned in the magazine's short run. But your screen career began several years before, after years of distinguished stage experience?

Jeff: Yes, that was The Robe in 1953.

Posted at 02:20 PM in Kinema Archives | Permalink | Comments (0)

From Professor Kinema...

He was the one person who instilled my personal interest in the Cinema. I had the extreme pleasure to meet him on several occasions. I even got to interview him. The results of the interview morphed into five Professor Kinema shows.

In just about all interviews he's had, he always related the story of how the direction of his life was truly altered when he attended his first theater showing of King Kong in 1933. As a kid, I underwent a similar life and career revellation when I caught my first screening of The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad.

The film was showing during a Saturday afternoon 'kiddie matinee' in the early 1960s, a few years after it's initial release in 1958. In the steady ruckus happening in the theater (as was always the case during Saturday afternoon kiddie matinees) I was enthralled by the sheer magical fantasy that was coming from the screen.

Coming to life before my eyes was a fire breathing dragon, a magician's concoction of a snake woman, two headed Rocs,a giant Cyclops, and an incredible sword fight between Sinbad and a skeleton. This cinematic fantastique was instilling an interest in the history and genres of movies within my pre-teen brain. I simply had to know how this movie magic was accomplished. Subsequently, I embarked on a personal magical journey of my own. This journey of the Quest of Cinematic Knowledge continues to this day.

The passing of special effects wizard Ray Harryhausen ended the reign of the three original Bat Packers (as Forry Ackerman always referred to them), which included Forry himself and Ray Bradbury.

Mainly through brief encounters at conventions I was able to meet Ray Harryhausen. I had the opportunity to thank him for instilling my interest in the cinema. He gladly acknowledged. While standing on line to have stills and other material inscribed, I couldn't help but overhear other conventioneers tell him the exact same thing.

Mainly through brief encounters at conventions I was able to meet Ray Harryhausen. I had the opportunity to thank him for instilling my interest in the cinema. He gladly acknowledged. While standing on line to have stills and other material inscribed, I couldn't help but overhear other conventioneers tell him the exact same thing.

During the weekend run of one particular Science Fiction convention in 2001 (that I was actively involved in), I was able to conduct an on-camera interview with him. I sat next to the camera that was framing him.

The interview lasted for about 1 1/2 hours. It was initially for the inclusion of a public access TV show titled Infinite Possibilities that friends of mine were producing. An unedited copy of the entire interview was made for me to utilize in my Professor Kinema show.

Portions of the interview morphed into a three-part show as well as two additional shows titled From Kong to Joe Young and The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad and Jack the Giant Killer - a Comparison. For the convention and the interview he had brought along with him several animation models for display. He allowed me to handle one of the skeletons that was used in Jason and the Argonauts. Harryhausen was impressed by my ready knowledge of his life and work as well as of the history of special effects in the Cinema in general.

The Kinema Archives contains many stills, books, magazines, posters and lobby cards that Ray was happy to inscribe for me. One item was a book that I had found at a yard sale, The Seven Voyages of Sindbad the Sailor. Published in 1949 (the year I was born as well as the year Mighty Joe Young was released) it had nothing to do with the film The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad. Harryhausen had never seen it. He looked it over and on my request inscribed it to me. He wrote "A wonderful book. I wish I had it when making the 7th Voyage. Best wishes! Ray Harryhausen."

Copies of the three part Ray Harryhausen interview, plus two other shows: From Kong to Joe Young and The Seventh Voyage of Sinbad and Jack the Giant Killer - a Comparison Professor are available. Contact Professor Kinema (Jim Knusch) through his Facebook page.

Posted at 11:00 AM in Kinema Archives | Permalink | Comments (0)

O, creator of Hecate, Damkina, Marduk's Messenger ... tem-khepera, khnemu ... Beelzebub in the netherworld ... Satan in Gehenna ... Controller of seven thousand and seven curses and talismans ... and who is known to obedient desciples as Gangida ... hold all your powers and those of your do-bidders ... and their familiars ... and cast a protecting shield above those gathered present...Pull back from airy bodies those vested with evil ... grant, O, magnificent one, no harm from the spells about to be witnessed. Direct them not! This faithful servent begs for Thy favor! Eftir irne-zet! Now with a free mind and protected soul, we ask you to enjoy Burn Witch, Burn!

Fritz Leiber's first novelette, Conjure Wife, originally appeared in the April, 1943 issue of Unknown Worlds , a pulp magazine. An expanded and revised version was published by Twayne Publishers in its Witches Three anthology in 1952, then issued as a stand-alone novel in 1953. Both hardcover and paperback editions, by a variety of publishers, continue in print to this day. Leiber's story is widely acknowledged to be a classic of modern horror fiction, included in David Pringle's Modern Fantasy: The 100 Best Novels, and in Fantasy: The 100 Best Books by James Cawthorn and Michael Moorcock. In The Encyclopedia of Fantasy, David Langford described it as "an effective exercise in the paranoid." Science Fiction author Damon Knight wrote:

"Conjure Wife, by Fritz Leiber, is easily the most frightening and (necessarily) the most thoroughly convincing of all modern horror stories... Leiber develops [the witchcraft] theme with the utmost dexterity, piling up alternate layers of the mundane and outré, until at the story's real climax, the shocker at the end of Chapter 14, I am not ashamed to say that I jumped an inch out of my seat...Leiber has never written anything better."

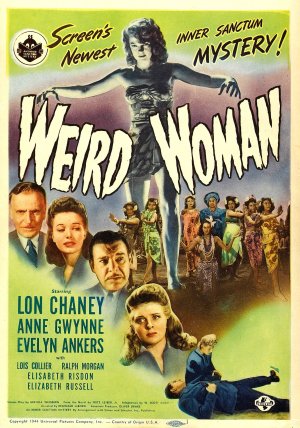

It was the original pulp novelette on which the screenplay of its first film version, Weird Woman (1944), was roughly based. Universal had initiated a B unit-produced series inspired by, and copying the name of, the popular radio series The Inner Sanctum. At the time, the series was in it's heyday and a series of Inner Sanctum books was equally popular. The Universal series, however, was promoted as a separate and original entity.

It was the original pulp novelette on which the screenplay of its first film version, Weird Woman (1944), was roughly based. Universal had initiated a B unit-produced series inspired by, and copying the name of, the popular radio series The Inner Sanctum. At the time, the series was in it's heyday and a series of Inner Sanctum books was equally popular. The Universal series, however, was promoted as a separate and original entity.

The first film of the series was Calling Dr Death (1943), which featured Lon Chaney, Jr, who went on to star in the entire series over the next couple of years. The director was Reginald Le Borg, under contract to Universal. Le Borg and Chaney had previously made The Mummy's Ghost (1943) and, after Calling Dr Death, moved on to the second of the Inner Sanctum series, Weird Woman. The series continued with Dead Man's Eyes (1944, again directed by Le Borg), Pillow of Death (1944), The Frozen Ghost (1945) and Strange Confession (1945). Of the entire Inner Sanctum series, Weird Woman is generally considered to be the best.

Weird Woman's screenplay was prepared by Brenda Weisberg and W. Scott Darling. The credits read "Screenplay by Brenda Weisberg, from the novel by Fritz Leiber, Jr" and "Adaption by W Scott Darling." The title of Leiber's novelette is not mentioned. Le Borg was handed the script a week before production was to begin and prepared for filming without reading the novelette. Via promotion, theater-goers were reminded that Lon Chaney, Sr was known as "The Man of a Thousand Faces," so now his son, Chaney, Jr was touted as "The Man with the Voodoo Voice." According to Weird Woman's pressbook, Chaney developed this talent in order to "project the voice of the supernatural," supposedly using a trick of ventriloquism taught to him by his father. Evelyn Ankers, the heavy of the story, carried the label "The Queen of the Horror Films."

Chaney was cast as Professor Norman Reed, a teacher of sociology at Monroe College in New England and the author of 'Superstition vs Reason and Fact.' In the novelette, his name is Norman Saylor, a teacher at Hempnell College who is preparing a paper, 'The Social Background of the Modern Voodoo Cult.' Ann Gwynn plays his wife, Paula (Tansy Saylor in the novelette), and Evelyn Ankers is Ilona Carr (Mrs. Carr in the novelette, referred to at one point as "...that libidinous old bitch"). It is not clear which of the female leads can truly be referred to as the weird woman. Since several women in the cast are involved in some sort of witchcraft, the film could more appropriately be titled Weird Women.

Chaney was cast as Professor Norman Reed, a teacher of sociology at Monroe College in New England and the author of 'Superstition vs Reason and Fact.' In the novelette, his name is Norman Saylor, a teacher at Hempnell College who is preparing a paper, 'The Social Background of the Modern Voodoo Cult.' Ann Gwynn plays his wife, Paula (Tansy Saylor in the novelette), and Evelyn Ankers is Ilona Carr (Mrs. Carr in the novelette, referred to at one point as "...that libidinous old bitch"). It is not clear which of the female leads can truly be referred to as the weird woman. Since several women in the cast are involved in some sort of witchcraft, the film could more appropriately be titled Weird Women.

Ann Gwynne proves to be the victim-weird-woman while Evelyn Ankers proves to be the evildoer-weird-woman. Promotion featured a provocatively sinister-looking Anne Gwynne posed in a sarong, hands outstretched and exuding a diabolic nature that is not developed as such in the film. Yet the term 'Weird Woman' could ultimately refer to woman-kind in general, as it is with the women in the plot who are bewitched and bewitching. Reportedly, the confrontation sequence between Gwynne and Ankers proved to be a difficult undertaking because they were such good friends.

Ann Gwynne proves to be the victim-weird-woman while Evelyn Ankers proves to be the evildoer-weird-woman. Promotion featured a provocatively sinister-looking Anne Gwynne posed in a sarong, hands outstretched and exuding a diabolic nature that is not developed as such in the film. Yet the term 'Weird Woman' could ultimately refer to woman-kind in general, as it is with the women in the plot who are bewitched and bewitching. Reportedly, the confrontation sequence between Gwynne and Ankers proved to be a difficult undertaking because they were such good friends.

Weird Woman reached a new audience when it was included as part of the original SHOCK! package of 52 Universal titles released to television in 1957.

After the 1953 publication of the reworked Conjure Wife in hardcover, it was to be the inspiration of the definitive screen version nine years later. In the meantime, a Twilight Zone episode titled The Jungle appeared on the airwaves on Dec 1, 1961. It was based on a short story of the same name by Charles Beaumont, first published in 1954 in If magazine. It later appeared in Beaumont's collection, Yonder (1958).

Plot-wise there were similarities to Leiber's novel, with a few touches of Val Lewton's Cat People tossed in. The story involves actors John Dehner and Emily McLachlin in a tale of a hydroelectric company executive whose firm is moving into an African nation to build a dam. The native residents don't take to the idea. An early sequence focuses on the (conjure?) wife whose husband discovers and subsequently destroys her magic charms and talismans. All, save one, are tossed in a fireplace. They go up in little puffs of smoke and make the wife terribly upset. Other elements common to this TV episode and the later Burn Witch, Burn crop up, such as Dehner's pursuit by an invisible force. His ultimate demise happens at the teeth and claws of a ferocious beast (here a lion) who inexplicably manifests itself after first appearing in stone form. No credit is given to Leiber.

In London the following year, two weeks before the cameras were to roll, writer George Baxt was handed a script written by Richard Matheson and Charles Beaumont. Director Sidney Hayers was dissatisfied with what he felt was an unworkable treatment of Leiber's novel and turned to Baxt for help. Hayers and Baxt had previously worked successfully together on Circus of Horrors (1960).

Like Le Borg almost two decades earlier, Baxt had not read Conjure Wife. His task was to take the Beaumont/Matheson script and 'doctor' it, removing what was felt to be inane dialogue. For example, the professor's wife is confronted by her husband, who demands that she give up her witchcraft and voodoo and destroy her magic symbols, talismans, charms and so forth. An exact quote from the novel's text, also in the script, was "But couldn't I just quit by degrees?" This was changed to, "Couldn't I just taper off?"

In an interview I had with him in his NYC apartment, Edgar Award winning author George Baxt related his involvement with what was to eventually released as Burn Witch, Burn:

In an interview I had with him in his NYC apartment, Edgar Award winning author George Baxt related his involvement with what was to eventually released as Burn Witch, Burn:

"It started with a call from an agent. I was living in London at the time. British director Sid Hayers had a script based on Fritz Leiber's Conjure Wife that was prepared by Charles Beaumont and Richard Matheson. The working title was Night of the Eagle. I previously prepared the screenplay for Circus of Horrors, also directed by Sid. The association was a good one. Both Beaumont and Matheson were established, well-known screenwriters, yet they came up with an unfilmable treatment. I was given two weeks to deliver a product and, needless to say, I had to work quickly. I had never read Leiber's novel. Work on the script continued during principal photography with additional pages and revisions delivered to the set on a daily basis.

(Note: I didn't ask him if Hayers or Baxt had seen and were familiar with Weird Woman of 1944)

"The original actress who was to play Tansy was June Allyson. Because of personal problems she was dropped and replaced by Janet Blair. Peter Wyngarde (Norman Taylor) was also cast as a replacement when the original actor became ill. Additions to the script that I was responsible for were the sequence in the graveyard and Tarot-card-burning scene. I thought the graveyard scene was handled well on the screen. Sid wanted me on the set throughout the shooting of the faculty bridge game. Margaret Johnston (Flora Carr) was the heavy of the story and it was important to the plot that she be positioned within the frame, appearing menacingly. Throughout she was constantly casting leery glances at Peter Wyngarde. The whole sequence was put on film in about an hour. I suggested at one point to place the camera behind the fireplace shooting out at the players (The Old Dark House-type of shot). As far as the eagle pursuit sequence goes, I originally didn't like the way it was handled, looking phony. Now, I think it was impressive."

Mention should also be made of the eagle that assays the role of the giant 'demon bird' who pursues Peter Wyngarde. It was a golden eagle named Lochinvar, trained especially for film and TV roles. The shot of the eagle bursting through the door was achieved by punching a glove puppet through a miniature of the door. There are only a few frames of this sequence before a very quick cut to a shot of an actual eagle in a miniature of the hallway, but the shape of a hand and wrist can just be made out in silhouette. Also, when the eagle is briefly shown in flight, a thin cable is visible attached to one of it's feet, guiding it's path. All in all, the complete sequence was effective for a film of it's day.