Zombos Says: Very Good

Zombos Says: Very Good

I looked forward to watching the antics of the Three Stooges every weekday afternoon, after school, on WPIX Channel 11's Three Stooges Funhouse show hosted by Officer Joe Bolton. Of course Joseph Reeves Bolton wasn't really a police officer (though he did have me fooled back then), but a children's TV host. He provided ample warning during every show to not do what the Three Stooges did; they were trained professionals using rubber wrenches, precise timing, and fakery for all those eye-pokes and bitch slaps.

Maybe it was the obvious impossibility of never being hurt by all those hand saws, crowbars, and planks of wood assaulting their heads and limbs, or maybe I was just smarter than the average bear as a kid, but I knew they weren't really hurting each other no matter how hard they worked at making it look real. But boy was it (and still is) so damn funny watching them go at it.

Their unique brand of situation-deconstruction and catastrophic action, perpetrated in homes, businesses, and in the streets, created a platform for havoc anyone could understand. Their visual interplay of physical timing and incongruous behavior, honed by repeated performances on vaudeville stages, and a total disregard for any sophistication whatsoever, is, simply put, sublime. Elements of farce, slapstick, and poke-in-the-eye punnery were served up buffet style, with a touch of social comment and topicality, as a nonsensical bricolage cemented with mirthful torment. Their comedy, even today, creates a contradictory raison d'etre of outrageousness that still bewilders non-fans while leaving new and life-long fans of the Three Stooges' knuckeheadedness in stitches: the more they engage in their nonsense and bodily assaults, the more we laugh (most of us, anyway).

Not many critics will dare derive sub-textual meaning from such nonsense (and body blows), but what makes the Three Stooges timeless is an everyone-yet-no-one duality they project as they struggle with themselves, the situation they find themselves in, and the unfortunate people they involve in their endless reaching for the good-living markers we all strive to attain. They dupe others, are duped by others, and they never catch a break (actually once or twice they did), or a clue, no matter how hard they try; and the harder they try, the worse it gets.

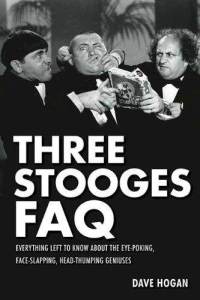

Dave Hogan's Three Stooges FAQ: Everything Left to Know About the Eye-Poking, Face-Slapping, Head-Thumping Geniuses hopefully isn't everything left to know about the Three Stooges, but it will soitenly keep you busy reading about every Columbia Pictures two-reeler (around 20 minutes each, they made 190 of them), the full-length movies (they appeared in 25 of them), and the notable victims the Three Stooges plied their unique style of comedy to.

Hogan wisely doesn't waste time trying to explain the Three Stooges or apologize for them. Instead he gets into the heart of it, first with a brief timeline of events leading to their formation as the team we recognize today, and then through a themed arrangement of all 190 Columbia Shorts into chapters such as The Stooges on the Job, The Stooges Go to War, and The Stooges Puncture High Society. There are thirteen themed chapters in all, with each short within its theme chronologically arranged and described.

He also explains the context of the times each short originally appeared in, providing information that is vitally important for understanding whatever subtexts an analysis, going beyond their simple zaniness, would reveal. He also points out the better usage of camera movement, editing, lighting, and locale in those shorts these elements are notable in. In general, the earlier shorts are better produced and better budgeted than the later ones, but some later ones do shine with brilliance.

Another basis for appraising each short is who directed it and wrote it, and Hogan supplies the information and the critical analysis, which almost always boiled down to how much money and time Columbia was willing to spend (much less as the years moved on) on any given short, and how creatively inventive the production team could be given the circumstances.

Which brings us to the Curly versus Shemp argument. After reading Hogan's book you will easily realize there is no argument to be made. Both Curly and Shemp were geniuses in their respective comedic personas, and both gave the Three Stooges a particularly effective zing to the trio's combined insanity by their presence. Rather, one should wonder, as Hogan points out, how Columbia strung Moe, Larry, and Curly along, year after year, never telling them how popular they really were. Never offering the Three Stooges a contract longer than one year, Columbia never gave the Three Stooges a raise, arguing the shorts were at death's door any minute because of changing times and audience preferences.

Throughout the book are sidebars highlighting the performers who appeared with the Three Stooges: there's Harold Brauer (Big Mike in Fright Night); Lynton Brent (the con man in A Ducking They Will Go); tall Dick Curtis (Badlands Blackie in Three Troubledoers); Phyllis Crane, who appeared in the Stooges shorts during the 1930s (wait, does that sound right?); and James C. Morton, who worked with the Little Rascals and Laurel and Hardy. He appears as the beleaguered court clerk in Disorder in the Court. Although you may recognize the faces, their sidebars provide the career information you probably don't know.

Here's an interesting tidbit to ponder: Hogan, in his timeline, notes that both Larry Fine and Moe Howard were pursuing studio contract negotiations in 1934; Larry (on behalf of Moe) was in negotiation with Universal Studios, and Moe (on behalf of Larry) was in negotiation with Columbia. Both Universal and Columbia signed on the dotted line, but since Columbia signed first, the Three Stooges wound up at Columbia. To any monsterkid worth his salt, and seeing how popular the Abbott and Costello Meet Frankenstein movie turned out, the question would be what might have been?

It took a long time for the shorts to die. Year after year, the Three Stooges did their best for Columbia and received no royalties as the sole rights for their shorts rested with Columbia. Columbia even had the foresight to claim sole rights across any and all media formats, then and in the future. By 1957, Columbia killed its shorts division and the Three Stooges were shown the front gate. After 24 years of money-making for Columbia,they were fired immediately, with no party, no thank you, and no royalties to bank on.

And yet the Three Stooges are more popular today and their Columbia shorts haven't been off the air since they were sold to television. So, it looks like Moe, Larry, Curly, Shemp, and the rest, got the last nyuck! nyuck! nyuck! after all. Good work, boys!

Note: My favorite short is Three Little Pirates. I dare anyone to say this naughtical bromance isn't the funniest, weirdest, and most outrageous episode in the Three Stooges canon. It's surreal, funny, and it's the last time Curly was at the height of his game, even though it was during his illness.

Zombos Says: An enjoyable, informative read.

Zombos Says: An enjoyable, informative read.

Before I say one word (well, okay, after these few words), if you are a horror fan worth any street cred, you need to read this book, savor it, dog-ear and highlight it. Brian Patrick Duggan is a passionate and experienced author with his subject matter, and McFarland has published a winner with his monumental work, Horror Dogs: Man’s Best Friend as Movie Monster. Even if you only have a significant horror movie hound in your life, then here is the perfect gift to give for the holiday season.

Before I say one word (well, okay, after these few words), if you are a horror fan worth any street cred, you need to read this book, savor it, dog-ear and highlight it. Brian Patrick Duggan is a passionate and experienced author with his subject matter, and McFarland has published a winner with his monumental work, Horror Dogs: Man’s Best Friend as Movie Monster. Even if you only have a significant horror movie hound in your life, then here is the perfect gift to give for the holiday season.