Zombos Says: Good

Zombos Says: Good

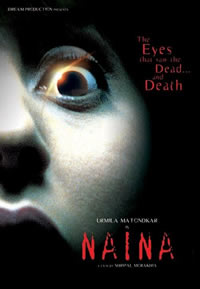

It took a few attempts to get Shripal Morakhia’s Naina into the DVD player. After the first bottle of Claret, my coordination deteriorated rapidly. I finally loaded the disc and Zombos and I were soon watching this intriguing Bollywood Horror remake of The Eye.

With a matter-of-fact tagline that reads, “Twenty years of darkness, seven days of hell, no one could survive it, SHE DID,” we did not have very high expectations. But the Claret made us stronger and more daring.

Then there are the cultural differences: how would a Hindi version of The Eye fit in with the melodramatic and religious aspects of Bollywood cinema? And most importantly of all, would there be singing and dancing?

“Bring on the dancing and singing Gopis,” hiccupped Zombos. “If I could stand it in Rocky Horror, I can stand it here.”

“There were no Gopis in The Rocky Horror Picture Show,” I told him.

“Not dressed as such, but the premise is the same.”

“Point taken,” I conceded. “But there are no Gopis, nor singing or dancing in this movie.”

“What? Impossible! I thought that was a contractual requirement for every Bollywood movie?”

“Apparently horror movies are excluded from that requirement.” I said.

I started the movie.

The opening shows the accident that leaves young Naina blind, intercut with a bloody cesarean-section of a still-born baby girl that suddenly comes back to life just as Naina’s parents are killed in an accident. Then there is an eclipse of the sun. We move ahead years later to a point where Naina is ready to undergo a cornea transplant operation.

“I am already confused,” said Zombos.

I refilled his glass. “There, that should help.”

Urmila Matondkar plays Naina Shah with a touch of melodrama—after all this is a Bollywood movie—and grandmotherly Mrs. Shah (Kamini Khanna) is constantly by her side. Yet the coloration of the movie, the cinematography, and, to some extent the somber, bittersweet, piano score give this movie a J-Horror style.

Naina speaks briefly to a boy in the hospital who is undergoing numerous brain operations, before she undergoes surgery to restore her sight. After the operation she begins to see dark figures through her blurry vision. These figures lead patients away. She also hears spooky sounds and sees dead people. Every dead person she sees is dressed in crisp white, neatly-pressed, clothes. It’s comforting to know there are laundries in the after-life.

Mrs. Shah quickly pulls out the eligible bachelor photos for Naina now that she can see, and starts working the old marriage magic on her. But Naina is becoming more and more distraught as her visions become more frightening. As Hindi cinema tradition would have it, the psychiatrist Mrs. Shah brings Naina to for help is handsome, eligible, and immediately infatuated with her loveliness—it’s love at first sight for both of them. A somewhat derailing Love Boat–styled romantic montage ensues and the horror is put on hold while love is in the air.

“Wake me when we get back to the dead people,” said Zombos.

I took a long sip of Claret. And another long sip of Claret.

Eventually Naina sees more and deader people and now they see her. From hanged men dressed in clean white clothes in restaurants, to little girls with little curls in hallways asking, “Have you seen my mommy?” Understandably, she becomes more distraught. Her psychiatrist boyfriend thinks it’s all in her mind (no, really?) and she can’t convince Mrs. Shah that those creepy black figures and talkative dead people are driving her to new heights of over-acting.

Then there’s the elevator scene.

It works well and puts you on the edge of your seat with its scary encounter in a tight spot. After that she’s back in the hospital and seeing more creepy black figures. A walk through the morgue as she follows eerie sounds and black figures is done with her as the only moving figure in a frozen room of doctors, nurses, and bodies in various stages of dissection. Gruesome.

At this point in her travails, she begins to question God. You don’t see much questioning of God in American horror movies unless some victim or madman is yelling expletives. She questions why God is showing her these sights. He tells her it’s time for the intermission.

No, I’m just kidding you, but the movie does stop—remember this is a DVD—with a big “Intermission” shown onscreen. You certainly don’t see this in American Horror DVDs or movies either.

I waited to see if a dancing bag of Buttery Sally Popcorn and Mr. Straw jumping into a cup of Coke would appear, singing “Let’s all go to the concession stand and have ourselves a snack.”

“Thank god,” said Zombos. “I really need to take a p—”

“I’ll get more Sherry and Coke.”

“Capital idea!” he said, hurrying to the bathroom.

INTERMISSION

While we wait for intermission to end, let me direct your attention to how this movie caused a lot of concern when it was released:

NEW DELHI (Reuters, 2005) – Indian eye doctors have asked a court to ban a movie in which the heroine sees ghosts after a cornea transplant, saying it will scare off donors and patients. The All India Ophthalmological Society complained to Delhi’s high court that the movie “Naina” (Eyes), starring Bollywood bombshell Urmila Matondkar, would reinforce myths about cornea transplants, The Times of India said Friday. “This movie could create a fear psychosis among cornea recipients and their relatives as well as among potential eye donors,” ophthalmologist Navin Sakhuja told Reuters. Would-be donors could be frightened off, afraid their eyes would “live on after they are dead,” said Sakhuja, a member of the society. “We have a huge backlog of people, particularly children, waiting to get new corneas. His movie adds to misconceptions and could hurt efforts to get them those corneas.” Naina’s director says the heroine’s visions after the transplant following 20 years of blindness are caused by what the donor had seen and experienced in life. “If such objections are taken into account, no horror film will ever be made,” the Times quoted Shripal Morakhia saying. The court is due to hear the case Wednesday, but the movie was released nationally Friday. India needs 40,000-50,000 corneas a year but only 15,000 are donated. Hindus believe in reincarnation and that what they do and how they behave in this life affects the next. Doctors say some people fear they will be reborn blind if they give up their eyes.”

END OF INTERMISSION

Now let’s back to our movie, shall we?

Naina is riding the train, talking to the psychiatrist boyfriend on her cell phone, when a revelation occurs, forcing her to suddenly question not only God, but who she is and the person who donated the corneas. Naina drags her reluctant boyfriend along to a place she’s seen in a vision. She stops being a victim and becomes resolute in finding answers. This sudden shift in the story is surprising and suspenseful, and adds an intriguing layer to it. Naina overcomes her fear as she investigates what happened to the eye donor, learns why dead people are attracted to her, and seeks to complete a broken cycle of reincarnation, even as those black figures begin to congregate in larger numbers.

Naina is similar to Premonition and Sixth Sense, but the mixing of J-Horror elements with Bollywood-Horror makes a story that’s part horror, part mystery, part ghost story, and worth a view by any horrorhead looking for something out of the ordinary.

And there’s no dancing or singing, either.

Raimi proves once again who’s your Superhero Daddy. He and the special effects crew create a swirling, spiraling, exhilarating ballet of web-slinging aerial combat that sizzles across the screen. In between the slugfests, he captures the difficult relationship between Peter and Mary Jane, the growing relationship between Peter and Gwen Stacy, and the trade-offs of being everyone’s hero.

Raimi proves once again who’s your Superhero Daddy. He and the special effects crew create a swirling, spiraling, exhilarating ballet of web-slinging aerial combat that sizzles across the screen. In between the slugfests, he captures the difficult relationship between Peter and Mary Jane, the growing relationship between Peter and Gwen Stacy, and the trade-offs of being everyone’s hero. Zombos Says: Fair

Zombos Says: Fair